Champs-Élysées Noir

The scandalous, blood-soaked story behind one of the world’s greatest art collections.

They had been hired to kill a young man named Jean-Pierre Guillaume. Dressed in trench-coats, the two assassins were waiting for him outside the entrance to the terminal at Paris-Orly Airport on the misty evening of 27 January, 1958.

When Guillaume eventually emerged from this giant, boxy modern building, he headed for the adjacent parking lot. He was a slender, dark-haired, not-quite-handsome twenty-three-year-old, who worked for Air France as a trainee airline steward. Watched by the two trenchcoated men, Guillaume got into a black convertible sedan, which had white-wall tires. As it sped across the parking lot, the watching men ducked into their own car, then tailed him onto the northbound side of the A106, a broad highway leading towards the low-rise heart of Paris.

Despite the mist, they were able to keep tabs on Guillaume’s distinctive vehicle. Just a few miles north of the airport, he stopped at one of the French capital’s many cafés, famed for their zinc-topped bars and smoky allure.

The men in the car behind him parked nearby. Intent on carrying out their plan, they followed Guillaume into the café.

And so began perhaps the biggest French socio-political scandal since the Dreyfus Affair more than fifty years earlier. Greed, perjury, sex, blackmail, and probable serial killing all featured in this labyrinthine drama, performed by a disparate and deliciously louche cast, several of whom concealed their criminality behind a façade of urbane, well-groomed charm. The cast encompassed socialites, down-on-their-luck war heroes, a call girl, millionaire businessmen, a fashion model, and at least one prominent member of the French government. In an era when critics at the highbrow Parisian movie magazine, Cahiers du Cinéma, were eulogizing a brand of visually and thematically dark American crime thrillers, which they labelled “film noir,” here was a real-life, Gaulois-scented noir that used the city around them as its backdrop.

What came to be designated as the Lacaze Affair had deep and tangled roots reaching back the better part of five decades before that winter evening when the two hired killers stalked their prey through the streets of Paris. The story began in 1911 when Paul Guillaume—whose surname the airline steward would acquire under bizarre circumstances—first met Joseph Brummer, the émigré Hungarian art dealer fated to change his life.

Back then, Paul worked as a clerk in a Parisian auto-parts store. No ordinary clerk, he had vague literary ambitions and a passion for visual art. These interests inevitably attracted him to the hillside neighborhood of Montmartre, where he made friends with several of the bohemian painters and writers who patronised its bars, restaurants, and cafés. In the front window of a laundry in that district, he spotted an improbable object. “I very much liked what I saw,” he wrote a few years afterward.

The object that caught Paul’s attention was a statuette, which turned out to be an example of Sudanese tribal art. It so fascinated him that he started reading everything he could find about the genre. His aesthetic interests and untapped entrepreneurial instincts stirred by the sight of that figurine, he arranged for his employer’s contacts in French colonial West Africa to send him other such sculptures. These were shipped to Paris along with consignments of rubber used for the manufacture of car tires. Like the Montmartre laundry that provided his eureka moment, Paul sold his African imports from the front-window of where he worked.

Through the type of chance connection around which individual fate often revolves, his poet friend Guillaume Apollinaire took the art dealer Joseph Brummer to the auto-parts store to view Paul’s latest exhibit. Brummer was so impressed that he struck a deal with Paul, who promised to give him first refusal on future imports.

Soon Brummer was a regular customer, enabling Paul to quit his job and devote himself to dealing in African tribal sculptures. Growing demand for these encouraged him to place adverts for them in colonial newspapers and in Parisian cafés frequented by officials on leave from French West Africa. So fashionable did African tribal sculptures become that many of the city’s up-and-coming avant-garde artists were prepared to barter their paintings for these.

Equipped with a stock of pictures by artists of the caliber of Pablo Picasso, George Braque, and Henri Matisse, Paul could now expand his repertoire as a dealer. His freshly opened gallery in the city’s fashionable Left Bank area began to show not just tribal sculptures, but also work by this significant new generation of European artists. Within just nine years of being introduced to Brummer, Paul had established himself as one of the most daring of the capital’s art dealers.

Part talent-spotter and part huckster, he drummed up interest in his exhibitions by editing and publishing Les Arts à Paris, a promotional magazine for which he and Apollinaire churned out articles, many of these appearing under inventive pseudonyms such as Violette de Mazia, Le Triangle Rouge, and K.H. Zambaccian. He saw the value of publicity stunts, too. By far the most flamboyant of these was an extravagant costume party emceed by the famous couturier and theater designer, Paul Poiret.

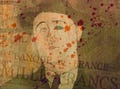

Blessed with an eye for marketable new talent, the owner of the eponymous Paul Guillaume Gallery championed the work of his Italian friend and protégé, Amedeo Modigliani, even going so far as to rent a studio for him. Out of gratitude, Modigliani painted a characteristically stylised portrait of the suited, behatted, and mustached dealer, head slightly cocked as he gazes at the viewer with foppish, purse-lipped self-assurance. The painter inscribed it with the words, “Nova Pilota” (New Helmsman)—a flattering, nautical allusion to Paul’s talent for steering young artists through the choppy waters of the art world.

One Sunday in 1920, Paul inadvertently sailed into far more perilous waters. During a trip to the voguish Riviera resort of Nice, he met Juliette Lacaze, a beautiful, charming, and drolly humorous young brunette almost a decade his junior. Unfortunately for Paul, he was a better judge of art than women. This particular woman’s surface appeal camouflaged her deeply unpleasant qualities. As he would later discover, she was avaricious, manipulative, and ruthless to a psychopathic level.

Her swift marriage to the celebrated Paul Guillaume represented just the next stage in a process of self-reinvention. Following the example of her doting brother, she had already swapped her mundane small-town existence for the excitement of Paris, where she had been working as a hatcheck girl in a nightclub. Matrimony swept her into a new social sphere, affording her the opportunity to begin remodeling herself—her clothes, her accent, her past, even her name. In a couple of portraits of the woman now known as Domenica Guillaume, the painter André Derain traced her swift transformation into an embodiment of Parisian chic.

Married though she was, Derain became the latest addition to her list of lovers. In the meantime, she dutifully contributed to the continued success of Paul’s business by sweet-talking gallery-goers into purchases. Her tastes were much less adventurous, however, than her husband’s. Under her calculating influence, Paul drifted away from the bohemian world and the art that had provided the launchpad for his career.

He and Domenica became habituées of an altogether different milieu. Uniformed chauffeurs ferried them around in limousines. Effete flunkeys trailed after them. And a troop of domestic servants ran their luxurious apartment. Hanging from the walls of the couple’s home was Paul’s collection of now hugely valuable contemporary French art, second only to that of his American client, Dr Albert Barnes, whose purchases were showcased in a newly created museum, located just outside Philadelphia.

For all the wealth and acclaim Paul garnered, he could not escape from the dispiriting realization that his heyday as an artistic arbiter lay far behind him. The advent of the 1929 stock market crash and ensuing economic depression marked a decline in his commercial fortunes as well.

Probably sensing that her husband’s career was on the downward slope, Domenica embarked on a very public infidelity with Jean Walter, a married friend and customer of his, who lived in the same apartment block as them. As a means of getting back at her, Paul threatened to donate his art collection to the French state unless she bore him a child. He even went so far as to enter into talks with the government about using his collection to create the country’s first museum of contemporary art.

Domenica appears to have been unable to have children, leaving her in a tricky situation. To prevent the collection slipping out of her grasp, she nonetheless announced that she was pregnant. A few months into the fake pregnancy, she got into the habit of lending it verisimilitude by stuffing a cushion under her dresses.

Ready for the day when she would have to pretend to go away to a maternity ward to give birth, she purchased a baby boy from a child trafficker, based on the rue Passier, not far from the center of Paris. The trafficker specialised in selling unwanted babies to the upper-classes.

Only a couple of months before the fake birth of her son, Domenica’s forty-three-year-old husband suffered an attack of appendicitis. There are good reasons to suspect that she deliberately delayed getting him to hospital. By then, a combination of sepsis and peritonitis had left him acutely sick. He died on October 1, 1934.

Now that Domenica was in control of her late husband’s money and possessions, she had no need of her adoptive son, christened Jean-Pierre but nicknamed Polo. For most of his first eleven years, he saw little of Domenica, whose maternal instincts were non-existent. Polo was of much less interest to her than her strenuous high society love life. Her lovers included Albert Sarraut, prime minister in two of the French governments of the 1930s. She also enjoyed an ongoing relationship with the besotted Jean Walter, though they made an odd couple.

His extramarital affair aside, Walter was as principled as Domenica was unprincipled. Owing to the refusal of Walter’s staunchly Catholic wife to grant him a divorce, he had to wait until her premature death before he could propose marriage to Domenica. By 1941 when he became Domenica’s second husband, his swelling bank balance and precious art collection had made him an even more rewarding catch for her.

In parallel to his flourishing career as an architect who mainly constructed hospitals, Walter had bought mining rights to land in Morocco. His purchase had been made against the advice of professional geologists, yet his audacity, self-belief, and perseverance had lately been rewarded. Vast reserves of high-grade lead and zinc had been discovered in what would be dubbed the Zellidja Mines, which he ran in collaboration with his grown-up son, Jacques.

Some of the profits from his Moroccan venture were used to create the Zellidja Scholarship Foundation, a lavishly-endowed and large-scale program of travel grants for impoverished French schoolchildren. Jean Walter’s altruism also manifested itself in his treatment of Domenica’s son. Conscious that Polo had never been officially adopted, Walter insisted that he and Domenica should go through the legal process necessary to formalise the arrangement.

After years spent living with a nanny in the south of France, Polo moved in with Domenica and Jean Walter once the war ended. But the benevolence of Polo’s new stepfather could not compensate for his mother’s resentful attitude towards him. To her, Polo was an unwanted burden, a source of disruption in the palatial and opulent apartment that she and her husband had taken on the Avenue Gabriel—close to the Champs-Élysées, among the city’s grandest neighborhoods.

Keen to punish Polo for intruding on her fastidiously ordered household, where servants could be fired for slightly repositioning a table, Domenica devised cruel ways to embarrass him in front of his schoolfriends. She would often give him no pocket-money, or make him wear one of her conspicuously feminine hand-me-down overcoats.

If she thought these petty humiliations would cajole him into becoming another of her decorous possessions, then she was misguided. Polo reacted by arguing with her, flunking exams, chasing girls, and getting kicked out of a string of private schools. The fractious relationship between him and Domenica culminated in the moment when she told him that he wasn’t her son, that Paul Guillaume wasn’t his father, and that his real mother “must have ended up on the streets after being knocked up by some wretched delivery boy.”

No wonder Polo was desperate to leave home as soon as possible. He tried to support himself with sorts of casual employment—as a factory worker, a dishwasher, a film extra, and a distributor of handbills. At the age of twenty, he enlisted in the army and became a junior lieutenant in the paratroop corps. He wound up being sent to Algeria, where a bitter insurgency against French colonial rule had been underway for several months. His well-connected mother apparently asked the general in charge to make sure that he was exposed to combat.

Serving in Algeria, Polo earned commendations for bravery yet provoked allegations of brawling, theft, and mistreatment of Algerian non-combatants, prompting one of his officers to refer to him as a “devoyé”—a delinquent. The reference featured in a letter to Domenica, who had begun to compile a dossier on Polo. Her motive lay in her miserliness. Appalled by the prospect of her now estranged son one day asserting his legal right to acquire half of her first husband’s art collection, she appears to have set about trying to avert that possibility through a devious legal ruse. If Polo could be shown to have committed a serious crime, she’d have the legal right to revoke her adoption of him, disinheriting him in the process.

While Polo was away from Paris, Domenica embarked on another adulterous relationship. On this occasion she chose a much younger man whose guileful self-interest led him to overlook the sagging blowziness that had replaced her one-time beauty. Her new lover was Maurice Lacour, a debonair forty-year-old with the face of a dissolute cherub. Formerly a member of a pre-war fascist-sympathizing terrorist group called Les Cagoules, he enjoyed a thriving career as a quack doctor and therapist who claimed to be adept in “the secrets of Siberian shamanism.” His clientele mostly consisted of women from Parisian high society. Before long, the self-styled Dr Lacour—said to derive most of his income from drug-dealing—had Domenica hooked on medication prescribed to relieve the pain caused by the onset of rheumatoid arthritis.

She contrived to move Lacour into her marital home and accompany her and Jean Walter on their regular trips to Morocco and elsewhere. “I’d willingly throw him out of the window,” Walter confessed to friends, but he didn’t dare provoke one of his wife’s ranting outbursts. He even allowed his wife to bully him into agreeing to have his heart problems treated by Lacour, who prescribed tablets that made him dangerously ill.

On the evening of June 8, 1956, the ubiquitous doctor joined Domenica and her husband at the Paris Opera for a gala performance in honor of the King and Queen of Greece. Joining Domenica and her escorts was her brother, Jean Lacaze, and his immensely rich girlfriend, fifty-eight-year-old Margaret Biddle. A close chum of Domenica’s, she was the ex-wife of the former US Ambassador to France. She happened to be a major investor in the Zellidja Mining Company, where Lacaze had become a senior employee. Rumor had it that she was unhappy about the way that the company was being managed, her unhappiness perhaps stoked by Lacaze.

During her trip to the opera, Biddle reportedly felt unwell and received treatment from Lacour. Not long after returning home, she collapsed and died of a cerebral haemorrhage. Suspicious though the circumstances of her death were, it was ruled as being from natural causes.

Just a year later, Domenica and Lacour would be associated with another suspicious death. It occurred during a trip to the country retreat owned by her and her husband, who were accompanied by her boyfriend. At the nearby town of Souppes-sur-Loing, the three of them stopped at a favourite restaurant of theirs. Walter encouraged the others to go into the dining-room while he crossed the road and bought a newspaper. He was waiting for a break in the heavy traffic when a car swerved and hit him. The impact hurled him into the air. Despite landing on his skull, he was still alive when Domenica and Lacour rushed out of the restaurant and took charge. Refusing offers to ring for an ambulance, the couple insisted on driving him to hospital, but they arrived too late for him to be saved.

Hindsight isn’t flattering to Domenica. Her failure to get another of her wealthy, persistently cuckolded husbands to hospital in time doesn’t seem like a case of bad luck. It doesn’t seem like a coincidence either. It seems more like a cold-blooded killer’s modus operandi.

With her husband out of the way, Domenica headed for Zellidja’s Paris offices. Her brother and her lover went with her. They made sure to arrive outside opening hours. Nobody but the doorman was on duty.

Sequestered in Walter’s workplace, Domenica and co used the opportunity to stage a partial coup. A few days afterward, she flourished a letter supposedly in his handwriting which, luckily for her, bore an uncanny resemblance to hers. The letter fired his son and son-in-law from their management roles within the prestigious Zellidja Scholarship Foundation. They were replaced by Lacour—whom Walter hated. It was an appointment that presented Lacour with ample scope to advance his political ambitions.

No such shenanigans were required with Walter’s will. He had already named Domenica as his principal beneficiary. A believer in the notion that inherited money is “morally damaging” to the recipient, he left nothing to his son or stepson, and only modest amounts to his daughters.

The income from Zellidja, which some years added up to ten-percent of France’s annual overseas income, made Domenica one of the wealthiest women in the world. Even without including her deceased husbands’ collections of nineteenth and twentieth-century paintings, she was estimated to be worth around $112 million, equivalent to anywhere up to $4.6 billion in 2021 terms. Unwilling to surrender even a small proportion of this to Polo, whose alleged misdemeanors in Algeria hadn’t supplied her with a pretext for revoking his adoption, Domenica reached the conclusion that she would have him murdered instead.

Her new boyfriend was only too willing to help find a potential hitman. Lacour began by contacting a friend of his, Armand Magescas, the managing editor of a right-wing weekly magazine entitled Jours de France. Magescas put him in touch with Camille Rayon, a former comrade from the French resistance against the Nazi occupation, which had ended thirteen years earlier.

Erstwhile colleagues still knew Rayon by his wartime codename—“the Archduke.” During the occupation, he had been in charge of coordinating Allied parachute drops and clandestine flights to southern France. These days he ran a fish restaurant in the Riviera city of Antibes, where he was the Assistant Mayor. So substantial were the losses incurred by his restaurant, Magescas figured that Rayon would be tempted by the offer of a handsome payment for killing Polo.

Sure enough, the proposal piqued the interest of Rayon, who had an innate love of intrigue. He agreed to let Magescas introduce him to Lacour.

Rayon would later describe how Lacour had claimed to be acting on behalf of “an honorable family” which wanted him to arrange the disappearance of a junior lieutenant of the paratroopers who was “compromising the great national effort” in Algeria. The contract-killing was thus recast as a patriotic act liable to appeal to a man of Rayon’s background.

He and Lacour settled on a fee of thirteen million francs—as much as $1.4 million in 2021 currency. Lacour paid him slightly less than a third of it up front. The balance would be handed over upon completion of the job.

In November 1957, Rayon and Lacour traveled to the Algerian capital, where Polo was based. Lacour cooked up an excuse for being in Algiers and wanting to meet Polo for a drink at the famous Hotel Aletti. That gave Rayon the chance to observe Polo across the bar before carrying out the murder.

Right at the last minute, Rayon revealed to Lacour that he’d decided to delay the killing. He would instead wait until Polo had left the army and returned to civilian life in Paris.

Another two months would pass before the fateful evening when Rayon and Alex Trucchi put their plan into practice.

The day after they had tailed Polo from Paris-Orly Airport, Rayon headed for an address in the city’s swanky 17th Arrondissement. On the sidewalk outside 70 Boulevard de Courcelles, he rendezvoused with Lacour.

Rayon informed Lacour that he had strangled the young airline steward, weighted down his body with rocks, and dumped it into the river. By way of confirmation, Rayon presented him with the young man’s identification papers.

“You have done your country a great service,” Lacour said. He handed Rayon a rolled-up newspaper. Wrapped inside was a thick wad of hard-to-trace old bills, comprising another installment of the thirteen-million-franc payment.

Lacour noticed that Rayon was shivering uncontrollably. Seeing that this former war hero appeared to be in a state of shock, brought on by the previous night’s gruesome events, Lacour went into a drugstore and bought him some tranquilisers.

His shivering hadn’t been caused by traumatic memories of committing murder, though. It must have been provoked by the realization that he’d just double-crossed some exceptionally dangerous people.

When Rayon and Trucchi had followed Polo into the café less than twenty-four hours earlier, they found a spare table next to where he was sitting. Rayon then leaned over to him and asked if he was Jean-Pierre Guillaume, known to everyone as Polo.

The young man replied that he was.

“What we have to tell you may seem extraordinary, but it is true,” Rayon said. “We have been given the job of killing you.”

Rayon and Trucchi assured Polo Guillaume that they had no intention of going through with the plan. They proceeded to reveal that “a certain party” had offered to pay lavishly for his murder. And they suggested that he should go with them to some nice, cozy bistro where they could discuss his predicament.

Skeptical but worried nonetheless, Polo agreed to have dinner with Rayon and Trucchi.

At the bistro, Rayon explained how he and Trucchi had become entangled in the plot to murder him. Rayon went on to propose a scheme that was presented as Polo’s only hope of surviving the murder plot. The scheme entailed faking his disappearance and presumed murder, then collecting the money from Lacour.

Before consenting to participate, Polo insisted on talking the whole thing through with his stepbrother, Jacques Walter, who loathed Domenica. Jacques gave the scheme his blessing, so Polo registered at a Paris hotel under a false name. By hiding out there, he created the impression that he had vanished. At that point Rayon contacted Lacour and announced Polo’s death.

Lending substance to the notion, Jacques Walter got in touch with Domenica’s brother, Jean Lacaze. Jacques asked him to let her know that Polo couldn’t be found in any of his usual haunts.

Neither Lacaze nor Domenica bothered to notify the police about Polo’s disappearance.

Once Rayon had collected the remainder of the promised thirteen-million-francs, he and Polo boarded the famous Blue Train. They traveled from Paris to Antibes, where Polo could lie low at Rayon’s home. Aware of the danger they were in, Rayon spent some of his time there laboring over a handwritten statement, headed “To be given to the competent authorities in the event of my disappearance or death.” He proceeded to write about how Lacour had hired him to kill Polo. When he finished his statement, he mailed it to his close friend, a prominent attorney named René Moatti.

Disregarding Rayon’s instructions, Moatti showed the document to the public prosecutor, who passed it on to Jacques Batigne. This Paris-based so-called examining magistrate—the French equivalent to a district attorney—launched an investigation so discreet that news of it was kept out of the press.

Batigne interviewed Rayon, Lacour, and Magescas as part of his inquiry. Under questioning, Lacour and Magescas admitted meeting Rayon the previous November, yet they insisted that the three of them had only discussed a real estate deal.

Rayon could muster no evidence to contradict their story—just three-million francs wrapped inside a newspaper. Without anything to corroborate what he had told Batigne, the investigation was going nowhere.

Drifting back to Paris from Antibes, Polo decided to see if he could earn a living as a freelance photographer. His nonchalant charisma enabled him to obtain assignments from editors at publications such as Paris-Match magazine, but he was unable to make enough money. He compensated for the shortfall by passing dud checks in cafés and bars, which brought him further attention from the authorities.

At La Belle Ferronnière, a modish restaurant on the Champs-Élysées, Polo crossed paths with twenty-three-year-old Maïté (short for Marie-Thérèse) Goyenetch. She was a slim, easy-to-talk-with brunette. Until she fulfilled what she saw as her destiny to become a movie actress, she worked as a prostitute, trawling the bars around the restaurant where she met Polo. In his case, however, she appears to have regarded him not as a client but as a boyfriend.

They were soon meeting anywhere between two and three times each week. For him, their relationship was nothing more than casual sex, untarnished by jealousy about the other men in her life. His new girlfriend, on the other hand, grew possessive, her attachment to him likely strengthened by talk of his rich mother who collected paintings.

In mid-December 1958, Goyenetch paid him yet another of her annoyingly frequent visits. This time she had a peculiar story for him. She said she had recently been accosted by a stranger as she walked out of the hotel where she lived. For an attractive young woman in her line of work, there was nothing unusual about this. Instead of flirting with her, though, the stranger had presented her with a business card and told her that she must ring the number printed on it.

Goyenetch described how she had phoned the number and been put through to an elderly man who said he wanted to discuss something that would be of interest to her. She obliged by visiting the address she had been given. It housed the offices of the Zellidja Mining Company. There, she met Polo’s cadaverous uncle, Jean Lacaze, who revealed that he knew about her romance with Polo and about her line of work. The implication was clear—cooperate with him or else. He then offered her a large payment if she’d go to the police and file a complaint about Polo leading her into prostitution and living off her earnings.

She admitted meeting Lacaze several times and haggling over her fee. He had ultimately agreed to pay her two million francs as soon as she filed the charges. In the event of Polo being convicted, a further two million would come her way.

Polo reacted by going to the police. He took Goyenetch with him. She repeated her story to the detectives.

Enhancing its credibility was a subsequent witness statement by Dany Nicol, a petite and pretty nineteen-year-old fashion model friend of hers. Nicol talked about being present at the encounter between Lacaze’s go-between and Goyenetch.

On the basis of the description supplied by the two young women, the detectives launched a manhunt for the pipe-smoking go-between. It culminated in an identity parade, at which both women picked out the same man.

The man they had accused of being Lacaze’s intermediary turned out to be a police officer.

Lacaze put forward a very different version of his dealings with Goyenetch. According to him, there had never been a go-between. He said he hadn’t even been aware of Goyenetch’s existence until she had contacted him. In his version of events, she had told him about being beaten by his nephew and about lending six million francs to Polo, who hadn’t repaid her. Lacaze claimed to have scented a blackmail plot and refused to settle the supposed debt.

Dubious about Goyenetch’s story, the detectives began to investigate her. They discovered that, just a few days before the alleged encounter with the intermediary, she had approached various art galleries and made inquiries about Polo’s mother. What’s more, Goyenetch had visited Domenica’s apartment and asked to speak to her. Domenica’s butler had informed Goyenetch that his employer was on holiday. He had added that Jean Lacaze was dealing with all family business in her absence.

These discoveries led the police to cross-examine Goyenetch, who burst into tears and admitted to making up the story about the encounter with the go-between. She also confessed to persuading her friend to lie on her behalf, yet she remained adamant that Lacaze had offered to pay her for framing Polo. The story about Lacaze’s go-between had obviously been conceived as a means of hiding her role as the initiator of the conspiracy. She must have lost her nerve before she could set things in motion.

Despite Goyenetch’s evident unreliability as a witness, the police had come to believe that Lacaze was a key participant in a conspiracy against his nephew. Its objective, Polo realised, was to provide the necessary legal justification for Domenica to revoke his adoption and thus disinherit him.

To buttress the case against Lacaze and maybe also confirm Domenica’s involvement, the police set up wire-taps and surveillance on Lacaze and his attorney, André Jais. These confirmed the existence of a conspiracy and alerted the police to the participation of Irène Richard, Lacaze’s secretary. Along with Lacaze and his attorney, she was now in danger of being charged with suborning a witness, which carried a jail sentence of up to a decade.

Information from the wire-taps revealed that Lacaze was planning to make a downpayment to Goyenetch on January 14, 1959. With Goyenetch’s assistance, the police set a trap for him.

Numerous officers in cars and on bicycles watched her that afternoon as she made her way to a meeting with Irène Richard. The wire-taps had alerted them to the fact that Lacaze’s secretary would be driving Goyenetch to the home of another Zellidja employee, from where they’d pick up the cash.

As expected, Goyenetch was observed getting into Richard’s car. So far, so good.

On the way across Paris, though, Richard must have spotted the surveillance. She stopped her car and forced Goyenetch out.

Even though the jaws of the police trap hadn’t quite sprung shut, Jacques Batigne—the examining magistrate in charge of the case—decided that he already had enough evidence to prosecute Lacaze, Richard, and Jais. A little less than a year after his investigation of Camille Rayon’s allegations had started, he issued warrants for the arrest of these three conspirators.

Lacaze was the only member of the trio to be held in jail. Not that he languished there for long. Within days, his lawyers had succeeded in getting him released on health grounds, after which he was admitted to an exclusive private clinic.

Prior to his arrest on January, 20, 1959, the scandalous goings-on within his family had not surfaced in the press. Yet the arrest only exposed one aspect of the story—the possible charges against Lacaze for bribing a witness to commit perjury.

Bit by bit, however, reporters unearthed fresh facets of what the press were calling “the Lacaze Affair.” Foremost among these was Domenica’s plot to have her son murdered. Attempts by reporters to track her down proved fruitless, which only fueled interest in the unfolding scandal.

For the next two weeks, it monopolised the front-pages of French newspapers, thanks to its beguiling combination of upscale glamor, crime, big business, sex, art, and power. It spawned prominent coverage across the English-speaking world, too. Headlines about it appeared in the leading British dailies. Time Magazine, The New Yorker, and The New York Times all ran articles about it as well, the latter of these publications describing it as a “sensational case.” Even provincial newspapers in places such as Virginia and Texas carried gloating accounts of it.

Paris-based journalists covering the case tended to view it as a bomb that would not detonate until it went to court. The ultimate explosion appeared likely to send tremors through the government by exposing Domenica and her brother’s corrupt connections to people in the upper echelons of French politics and business. Inside the government, there was certainly sufficient anxiety for officials to feel the need to show a bulky, half-completed file on the case to President Charles de Gaulle. Several of his ministers admitted that he was horrified by what he read.

At last the press tracked down Domenica. She and Lacour had checked in to the Hotel Mamounia in the Moroccan city of Marrakesh. Pestered by journalists, Domenica made a reluctant statement to them.

In response to claims that she had fled from Paris, she said, “I always spend two months in Morocco. I see no reason to change my habits. The weather is lovely here. Anyhow, the whole affair is childish, and of no importance.”

A few days later, she and Lacour went back to Paris. On the morning of February, 5, 1959, they endeavoured to quell the escalating speculation about their activities by staging a big press conference at the Ritz Hotel. Domenica and her lover informed a throng of reporters that they and her brother were the victims of a series of blackmail plots. “I demand that full light be thrown on these machinations,” she said.

Far from exonerating her, the brightness of the spotlight shone on the case illuminated yet another murky aspect of it. This concerned a newly launched police investigation of the circumstances surrounding the death of Margaret Biddle three years earlier. In all likelihood, the investigation was triggered by a statement made by one of Lacour’s lackeys. The man had confessed to being instructed by Lacour to break into Biddle’s house on the night of her death and steal a package of documents concealed behind a painting. Even so, the Biddle investigation wound up being shut down before the dead woman’s body could be exhumed.

Unproven though the link between Biddle’s death and the Lacaze Affair was, it generated headlines as far afield as Australia. The unceasing torrent of newspaper articles, press photos, and television interviews had, by mid-February 1959, transformed the scandal’s main participants into celebrities. Maïté Goyenetch’s newfound fame even led to her being given half-a-million francs worth of dresses by the star fashion designer Ted Lapidus, who wanted her to be seen wearing them. And there was talk of Brigitte Bardot—the young French movie goddess—playing her in a big screen dramatization of the story.

Interest in the Lacaze Affair remained so intense that a large crowd filled the movie theater where Camille Rayon gave a talk about his role in the case. “I solemnly affirm that I have always spoken the truth,” he told his audience. “What I did, I had to do to save a man.” He added that friends in the French secret service had warned that his life may be in danger. “But I am not afraid of threats and will not be bought.”

At the end of the hour-long talk, Polo rushed onto the stage and embraced Rayon. “I wish that there were lots of men in France like Camille Rayon!” he shouted to the crowd.

Rayon’s talk prompted a rapid announcement by Domenica and her brother that they were suing him for slander. Lacour initiated legal action as well.

The target of these lawsuits wasted little time in dismissing them as “just a piece of face-saving diversion.” Rayon also expressed confidence in the magistrate investigating the case. “He will pursue the affair to the bitter end,” Rayon declared.

Conveniently for Domenica, the arrival of spring marked a sharp reduction in the amount of reporting on the scandal. Not because public curiosity had diminished but because new rules had come into force, restricting press stories about ongoing police investigations.

Journalists had to wait until Lacour was arrested before they could indulge in a fresh wave of coverage. On March, 13, 1959, Domenica’s lover became the first person in the entire convoluted saga to face criminal charges. He was accused of conspiracy to attempt murder. If found guilty, the judge had the option of imposing a death sentence.

A mob of reporters and press photographers witnessed Lacour being driven away in a police van, which took him to La Santé Prison. That evening he was visited by the leopardskin-coated Domenica, who shielded her face from the loitering cameramen.

Even with Lacour in jail awaiting trial, there was no confidence among journalists that the intricacies of the scandal would ever be unraveled. “Only one conclusion is reasonably certain: one of these days somebody will make a movie about it,” wrote an American journalist, whose prediction hasn’t so far been proved accurate.

Pessimism about the prospects of justice being enacted in the Lacaze Affair was well-founded. Domenica seems to used her links to the de Gaulle government to quash the scandal. In what must surely have been more than mere happenstance, there were three important developments. One: Batigne abandoned his long-running investigation. Two: the charges against Lacour were dropped on legally questionable grounds. Three: Domenica agreed to hand over to the French state 147 paintings from the Paul Guillaume and Jean Walter art collections—paintings by the likes of Picasso, Matisse, Modigliani, and Derain.

The impression that the wily Domenica had pulled off a sleazy transaction was accentuated by the French government’s suspicious insistence on keeping the terms of the arrangement confidential. Brokering it was the revered novelist-turned-Minister of Culture, André Malraux, an old friend of Domenica’s, who regularly lunched with her.

Rather than just donate the paintings, she sold them for a nominal fee, estimated at a mere fifteen-percent of their value. That small fee suited both Domenica and the French government. For the government, which sought to distance itself from the corruption associated with its predecessors, the fee offered a serviceable defence against accusations of hypocrisy. What made the nominal fee advantageous to Domenica was that it safeguarded her from potential lawsuits instigated by either her son or her second husband’s grown-up children. Under French inheritance law, they would have been entitled to make her reimburse them for the full value of the collection if she had either given it away or sold it for its market price.

Were the collection to be auctioned these days, it would raise far in excess of $1 billion, even without her first husband’s cache of African tribal art and several of his early treasures by Matisse and Picasso. Domenica had sold these long ago.

Possibly because she disliked the prospect of removing all of the paintings from her apartment at once, she arranged to surrender them in two batches—forty-seven in 1959, and a further ninety-nine in 1963. Another couple of years would pass before the pictures went on temporary public display in Paris. They were later moved to the Musée de l’Orangerie in the Tuileries Gardens, where they remain to this day. Few of the river of tourists that flows through the galleries are likely to be aware of the dark and convoluted tale of how those pictures ended up there.

Among the paintings on display is André Derain’s late 1920s “Portrait of Madame Paul Guillaume with a Large Hat.” From beneath her broad-brimmed sun-hat, perfectly color-coordinated with the rest of her outfit, Domenica peers through blue eyes, her glamorous features expressionless and remote. As one of her many lovers, Derain evidently discerned the glacial personality lurking beneath those fastidiously styled movie star features. His painting hints at the ruthless cunning that would enable her to dodge punishment for her crimes.

She was, however, powerless to evade the worsening rheumatoid arthritis that beset her during the 1960s and 1970s. It twisted her once elegant hands to the point where she could barely hold anything. In search of a respite from the pain it caused, she would instruct her chauffeur to drive her to the Place Pigalle, a notorious sexual and pharmaceutical marketplace, from where she purchased opium and cocaine.

Her monstrous treatment of Polo, now supporting himself by working as a press photographer, had left him surprisingly free from bitterness. He even had a yearning to reconcile with her after a decade-long estrangement. His opportunity came when he heard that she was lonely and keen to see him, so he arranged to visit her gigantic apartment on the rue du Cirque, just a short stroll from the Champs-Élysées.

He soon discovered that the prospect of belatedly establishing a proper mother-son relationship was not the reason for her being anxious to see him. She turned out to want to ask him if he’d be prepared to renounce his adoption by her. “I will compensate you, of course,” she assured him.

Polo got up from the table and walked out of the apartment. He would never see Domenica again.