Freudian Clips

An encounter with one of the best-known models used by the painter Lucian Freud, plus the hitherto untold story of how he ended up as the defendant in a court case.

Over Christmas about twenty years ago, I remember playing what my now elderly brother-in-law called “the handshake game.” This began with each contestant being allocated a prominent historical or present-day person. Anyone from Winston Churchill to Michael Caine. You were then expected to try to connect yourself to that person via the shortest possible chain of encounters, each link in the chain being represented by a moment when one person had the opportunity to shake hands with the next person in the sequence. For instance, I might’ve had a granny who had briefly met Churchill when he was campaigning to become her local Member of Parliament. That’d place me just a couple of handshakes away from him.

Though I’ve forgotten which targets we were given or who won our game, I do recall that our routes to the targeted people were pretty circuitous. Of course the game was a precursor of the now widely known concept of “six degrees of separation”, popularised by John Guare’s 1990 play and the equally brilliant movie adaptation of it. “I read somewhere that everybody on this planet is separated by only six other people,” says its heroine. “Six degrees of separation between us and everyone else on this planet. The President of the United States, a gondolier in Venice, just fill in the names. I find it extremely comforting that we’re so close.”

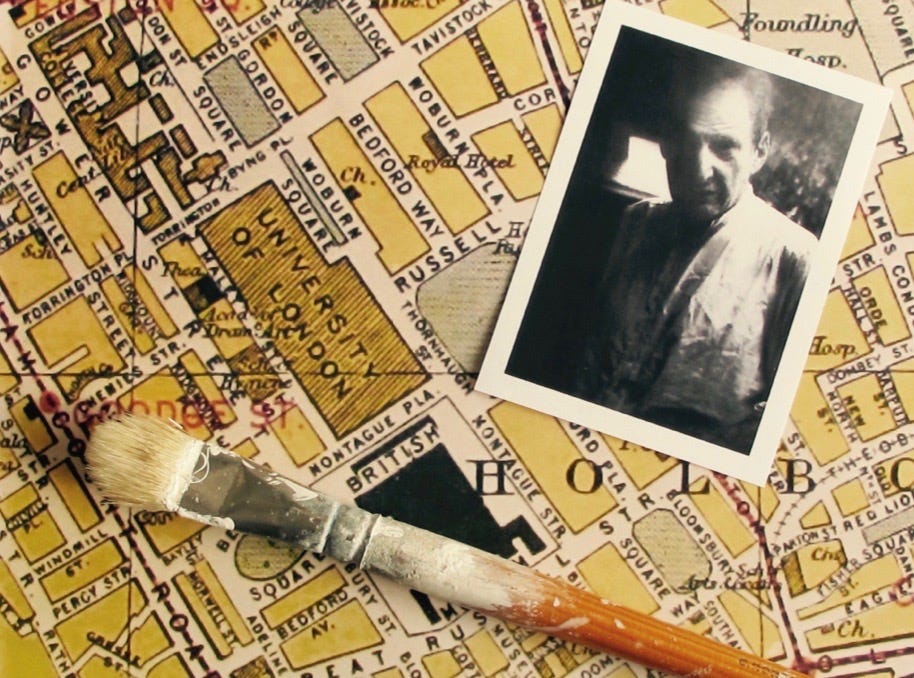

At least a dozen people—and those are just the ones I’m aware of—have brought me within no more than two handshakes of the artist Lucian Freud (1922-2011), grandson of the psychoanalyst, Sigmund. Judging by everything I’ve heard and read about the younger of these men, I’m glad I came no closer to him.

London’s South Bank—more specifically the base of the London Eye, that huge ferris wheel overlooking the river—was the setting for one of those occasions when I strayed within only a couple of handshakes of Lucian Freud. That evening I found myself in a queue of thirty-two guest speakers, waiting to board the wheel’s thirty-two pods. In the course of a single circuit, each speaker was due to deliver a short talk about a specific person who had been born outside London yet had gone on to play a significant role in the city’s history.

This brilliantly organised event was the brainchild of the arts impresarios, Suzette Field and Stephen Coates, the latter of whom has enjoyed a successful music career as the singer for the Real Tuesday Weld. Speakers ranging from the literary biographer Claire Tomalin to the TV presenter Dan Cruikshank had been recruited by them to hold forth on subjects as varied as the novelist Charles Dickens and the footballer Stan Bowles. I was there to talk about Paul Raymond, the Soho club owner, property magnate, and smut peddler, best-known for the Raymond Revuebar nightclub.

While I waited to board my assigned pod, I chatted with the rotund and friendly woman ahead of me in the queue. “Who are you going to be speaking about?” I asked.

“Lucian Freud,” she replied.

She immediately asked me the same question. When she heard my response, she unleashed a bawdy laugh and said, “So we’re both writing about dirty old men…”

I soon discovered that she was none other than Sue Tilley, a Job Centre supervisor and part-time writer who had been the subject of several of the large-scale nude portraits created late in Freud’s career. Whatever you think about them, they’re instantly recognisable as his paintings. The models’ inelegant poses are distinctive, bodies splayed like dead frogs on a dissecting table. And the colours are distinctive too, flesh tones streaked and blotched by various shades of white, not to mention pale greens and blues. These paintings—which cemented his reputation—could hardly be less flattering, a combination of their self-conscious ugliness and Freud’s lineage prompting critics to extoll his psychological acuity and unflinching view of humanity.

His nude portraits of Sue Tilley include a 1995 painting titled “Benefits Supervisor Sleeping.” It showed the woman whom Freud nicknamed “Big Sue” asleep on a faded Chesterfield, her breasts and stomach cascading towards the viewer. In 2008, it achieved an unlikely milestone. At the New York branch of Christie’s, where it was being auctioned, Roman Abramovich bought it for $33.6 million, making it the most expensive picture by a living artist at that time.

As Sue and I stood in the queue for the London Eye, she told me how she’d been introduced to Freud by Leigh Bowery, the Australian nightclub host and exhibitionist, whose biography she was writing. Freud already happened to be painting nude portraits of Bowery. Sue would soon become another of his regular models. But her reminiscences were abruptly truncated when the next of the London Eye’s pods glided into position and she was ushered aboard.

In the years since my brief conversation with her, another unexpected link to Freud materialised. It surfaced during a phone conversation with Ken Lee, a multi-talented octogenarian friend of mine, who had taught in art schools, designed sets for the Royal Opera House, and written a hit West End musical called Happy As A Sandbag. A devotee of nonfiction, he told me about the book he was reading—Martin Gayford’s Modernists & Mavericks, which portrays the postwar London art scene through the interconnected lives of various prominent painters, Freud among them.

“It’s odd reading a book where I’m so familiar with the world it’s portraying and where I used to know so many of the people he describes,” Ken said to me. “I think it’s very good, but he’s got a few little things wrong. There’s a bit where the author refers to Lucian Freud teaching at the Slade. Though Freud was supposed to be teaching us, he never actually did what he was paid to do. He’d just peer round the door into the studios and then walk away.

“I reckon he only took the job so he could get a central London parking space. I remember him having a flashy car—a Jag’ or something of that sort—which he’d leave in the college car park. Driving out of there onto Gower Street one day, he crashed into another vehicle. But instead of exchanging details with its driver, he just walked off and abandoned his car.

“Eventually, he was prosecuted for breaching the traffic laws. When news of his impending appearance at a local magistrates’ court reached the Slade, quite a few of the students—myself included—arranged to go to the hearing because we thought it might be fun.

“I’m pretty sure that nobody’s ever written about Freud’s little brush with the law. And I wonder how many witnesses to it are still alive.

“The magistrate ended up fining Freud and, in the process, coming out with a withering line that he must’ve rehearsed beforehand. It’s always stuck in my mind. ‘Mr Freud,’ the chap said, ‘your behaviour indicates that you might have benefitted from a course of treatment by your grandfather.’ ”