Meet the Mob

How the murder of two gangsters in a Democratic Party clubhouse spawned a coast-to-coast American television event that influenced The Godfather movies.

The bodies of Kansas City underworld boss Charlie Binaggio and his sidekick “Mad Dog” Gargotta were discovered at around 5:00 am on Thursday, 6 April, 1950. Both men had been shot in the head four times. Their murders, which had taken place in the Democratic Party Club on the North Side of Kansas City, made front-page news across America, partly due to the enveloping cloud of political scandal.

Before his violent death, Binaggio had gone from being a small-time gambler to a mobster with big-time ambitions, which led him to buy political influence within his chosen party. The high point of this came in 1948 when he facilitated the election of Democrat candidate Forrest Smith to the governorship of Missouri. For Binaggio, the ultimate objective was to take control of the police forces in Kansas City and St. Louis, where he would then be able to run his illegal gambling operation with impunity.

Despite the enormous publicity surrounding the Kansas City killings, nobody was ever held accountable. The press coverage did, however, stoke widespread anxiety about gangland violence and the emergence of powerful crime syndicates. Those concerns had already led the US Senate to set up an as yet inactive five-man, cross-party Special Committee on Organised Crime in Interstate Commerce.

Just under a month after the murders of Binaggio and Gargotta, the committee received generous funding, equivalent to around $6.5 million in today’s money. Under the leadership of the ambitious, recently elected forty-seven-year-old Tennessean senator, Estes T. Kefauver, investigators were hired and preparations were made for what would become a fifteen-month series of hearings in fourteen major cities from New York to Los Angeles. On the basis of previous research, Kefauver briefed the committee to focus on the illegal interstate gambling industry, described by him as “the life blood of organised crime”.

Unusually for that era, he allowed the public to attend the committee’s hearings. They kicked off on 28 May, 1950. First stop was Miami, where he and his colleagues set the pattern of subpoenaing prominent members of the local underworld. Even though some of the witnesses took advantage of their legal right not to incriminate themselves by testifying, the so-called Kefauver hearings unearthed evidence of ways in which the illegal gambling industry permeated the city. One bookmaking syndicate’s political connections were traced all the way to the Florida governor, Fuller Warren—a revelation that precipitated his downfall.

By March 1951 when the Kefauver roadshow rolled into New York, public interest in the hearings had blossomed to the point where the major national television networks started using them as a source of cheap yet compulsive daytime entertainment. Fewer than fifty-percent of American households owned televisions at that time, so restaurants, bars, and cinemas offered screenings of the live broadcasts as a means of attracting extra customers.

An estimated thirty million people dipped into the television coverage, giving them a taste of a lurid world most of them had never encountered outside pulp novels and crime movies. During the eight days in which these hearings were broadcast on five of New York’s seven television stations, audiences at Broadway shows dwindled, department stores emptied, and “Kefauver block parties” were held.

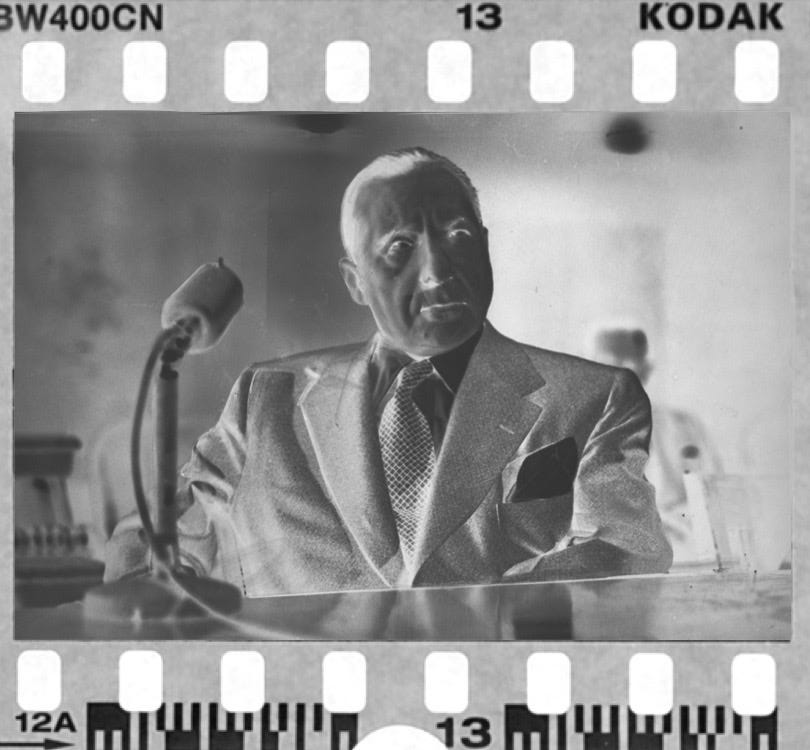

Among the parade of underworld bosses, street thugs, as well as crooked police officers and local government officials interrogated by the committee was Frank Costello, who had repeatedly been identified as a key member of one of the country’s largest illegal gambling syndicates. He was one of the committee’s most fascinating witnesses, not because of his candour but because of his peevish and menacing presence that was so at odds with his suave get-up. Also on conspicuous display was his prevarication, which culminated in him walking away from the witness table without permission, earning him a contempt of court charge. No wonder newsreel footage of his performance in front of the committee would many years later provide an invaluable tool for Marlon Brando while preparing for the role of Don Corleone in The Godfather (1972).

But the most talked-about witness at the New York hearings was probably the tough, Alabama-born former waitress, Virginia Hill Hauser, girlfriend of numerous gangsters, notably the late Bugsy Siegel. Wearing a mink stole, long black gloves, and a matching broad-brimmed velvet hat, she cut a stylish figure as she batted away the committee’s questions.

Invited to reveal whether she knew how her boyfriends made the money that enabled them to deluge her with cash and jewellery, she replied that she “didn’t know anything about anybody.” Her blunt and combative responses sometimes provoked laughter or applause from the large audience at the US Courthouse in Foley Square.

In the wake of her testimony, the leading television critic John Crosby wrote, “Senator Kefauver noted with some alarm that some segments of the populace showed a tendency to sympathise with the witnesses, no matter how shady their past. The one person who seems to have won universal acclaim after a stint before the cameras was Virginia Hill, which suggests this isn’t so Puritan a country after all.”

Once the committee’s gruelling coast-to-coast tour had finally been completed, Kefauver oversaw an 11,000-page report on the corrupt links between organised crime, law enforcement, and elected officials. Yet most of the recommendations made by him and his colleagues were ignored. Even so, the consequences of the committee were wide-ranging. It spawned vast numbers of salacious newspaper stories. It introduced the word “mafia” into common parlance. It ousted a few crooked politicians and police officers. And the television coverage of it earned its bespectacled, unflappably genteel but dogged chairman nationwide renown. Nowhere is this more demonstrable than in a December 1951 survey of Americans, which listed him alongside the Pope and Albert Einstein as one of their ten most admired men.

Kefauver deployed his newfound fame and popularity in a bid to try to secure nomination as the Democratic Party’s candidate for the 1952 presidential election. His campaign began with the headline-grabbing defeat of President Harry S. Truman in the New Hampshire primary. Kefauver would go on to win twelve of his party’s fifteen primaries, but in those days that was insufficient to clinch the nomination. It went to Adlai Stevenson, who ended up being defeated in the ensuing general election. Undeterred, Kefauver sought his party’s nomination in 1956, only to be defeated again by Stevenson, though he did become Stevenson’s running-mate in what turned out to be an unsuccessful challenge to President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Dwarfing the socio-political repercussions of the Kefauver hearings was their impact on popular culture. They unleashed a flurry of Hollywood crime movies purporting to be exposés of organised crime, the earliest of these being The Captive City (1952), which even featured a prologue and epilogue in which Kefauver spoke directly to camera. More than two decades later, the work of his committee would be immortalised by The Godfather II (1974), which used it as a central plot device and borrowed liberally from its cast of evasive hoodlums. In one of the movie’s most memorable scenes, a committee member asks an under-boss of the Corleone mafia family, “Were you at any time a member of a crime organisation headed by Michael Corleone?”

The mobster—played by the stocky and hoarse-voiced Michael V. Gazzo—affects an expression of squinting bewilderment as he replies, “I don’t know nothin’ about that. Oh, I was in the olive oil business with his father, but that was a long time ago…”