Monkey in the Middle

The electrical engineer, the chimpanzee, and the wacky race to broadcast the first transatlantic television spectacular.

Bleary-eyed from supervising the NBC television network’s election night programme, which had ended just a few hours earlier on the morning of 5 November, 1952, Charles H. Colledge, Jr, boarded a plane at Idlewild Airport in New York City. He was a bespectacled, New Jersey-born electrical engineer now in his mid-forties. Apart from the war years when he took a leave of absence to play a crucial role in the US Navy’s radar research project, Colledge had been employed by NBC ever since graduating, his status as a Columbia University alumni earning him the nickname “Joe College”. In his current capacity as Manager of NBC Network Public Affairs, Sports, Special Events, and News Production Operations, he was about to fly to London, where one of the trickiest assignments of his career awaited him.

From the moment he disembarked on the other side of the Atlantic, Colledge had a little under seven months to lay the foundations for NBC’s coverage of an event already obsessing most of the top brass at the American television networks. That event was the coronation of the young Queen Elizabeth II, whose 1951 visit to the United States had helped to generate widespread excitement about it among Americans.

Colledge’s mission was made a lot easier and cheaper by prevailing British copyright law, which ruled that the BBC had no control over the use of its footage. Getting that footage from London onto America’s small black-and-white screens would, however, be far from straightforward due to the technological limitations of the early 1950s. NBC couldn’t simply bounce live television coverage from continent to continent via satellite, because the means of doing that were almost a decade away.

In theory at least, the obvious solution was to pipe the coverage through existing transatlantic telephone cables, but the cost of doing that turned out to be prohibitive. Its $30 million price tag, equivalent to as much as £1.6 billion in present-day currency, was also way beyond the budgets of the rest of the North American television networks—NBC’s US rivals, CBS, DuMont, and ABC, as well as CBC, the Canadian state broadcaster. Colledge and his counterparts at these networks would have to make other arrangements if they wanted to screen the coronation. Given that videotape and digital technology lay in the future, they’d have to copy the BBC’s coverage of the event onto film, using a bulky kinescope machine—in essence a 16mm movie camera mounted in front of a television screen. The resultant reels of film would then have to be flown across the Atlantic.

Convoluted though the whole process of putting coronation footage onto North American television screens would be, Colledge and his rivals had one significant factor in their favour, namely the time difference between countries on opposite sides of the Atlantic. In flying from England to America, NBC’s film would be moving from Greenwich Mean Time to Eastern Standard Time, from noon in London to 7:00 am in New York. For that reason, NBC and the other North American television networks would have an entire day in which to screen coronation day programmes.

Before setting off for London on his preparatory mission, Colledge had been ordered by his bosses to find “a secret weapon” capable of getting NBC’s footage onto their network ahead of their American rivals. He soon identified the British-built de Havilland Comet as the plane that would give NBC the edge. Being the world’s only jet airliner, it would be able to cross the Atlantic faster than any other civilian aircraft. So Colledge submitted a request to charter one of these aircraft from BOAC (British Overseas Airways Corporation), the state-owned company that had a monopoly on them. But BOAC insisted on him trying out the plane before they’d rent it to him.

With just four weeks to go until the coronation, he arrived in Rome, ready to catch the final leg of the Comet’s regular Singapore to London flight. Next morning, though, he discovered that his plane had crashed shortly after take-off from Calcutta, killing all of its passengers. Since these aircraft had gone into commercial service exactly a year earlier, this was the third Comet to be involved in a disastrous accident.

BOAC had little choice but to suspend further flights by the aircraft until the cause of the crash could be identified. It was a decision that stripped Colledge of his secret weapon.

He responded by approaching the Bristol-based English Electric company and proposing to charter one of the Canberra jet aircraft they were supplying to the RAF and other airforces. As luck would have it, the firm was poised to sell a Canberra to the Venezuelan government, which turned out to be willing to help NBC in exchange for an exorbitant fee. Besides switching the delivery date to coronation day, the plane’s new owners agreed to its Venezuela-bound flight detouring to Goose Bay on the east coast of Canada, where it could drop off NBC’s film footage.

Plans were made for this precious cargo to be picked up from Goose Bay, loaded onto a souped-up, privately owned P-51 Mustang fighter aircraft, and flown south to Logan Airport in Boston, Massachusetts. There NBC had constructed a television studio from which they could broadcast the coronation footage.

Knowing that NBC would need additional material for its evening highlights programme about the coronation, Colledge also chartered a Pan American Airways DC-6B, which was scheduled to set off a few hours after the Venezuelan Canberra. To speed up the process of getting this second consignment of film onto American television screens, editing equipment had been fitted on the DC-6B. By the time it touched down at Goose Bay, the evening highlights programme would be ready for transmission.

CBS and CBC had meanwhile made equally complex arrangements for their broadcasts on coronation evening. Like NBC, CBS had hired an airliner to drop off its footage at Goose Bay, from where it would be collected by another souped-up P-51 Mustang and transported to a specially constructed television studio at Logan Airport.

In contrast to the fierce coronation-related rivalry between NBC and CBS, the two other less popular and well-funded American networks abstained from involvement in the race. DuMont stated that it would be scheduling no special coronation programmes, aside from references to it within news bulletins. And the executives at ABC struck a low-cost deal allowing them to transmit CBC’s coverage of the event.

CBC had arranged for its own copy of the BBC coverage to be taken to Goose Bay on an RAF Canberra. The film would then be picked up by a Royal Canadian Air Force jet and delivered to Montreal, where CBC had established its own coronation day broadcasting facilities.

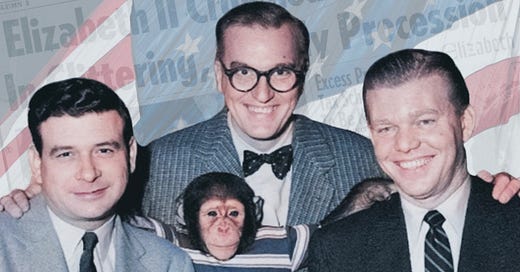

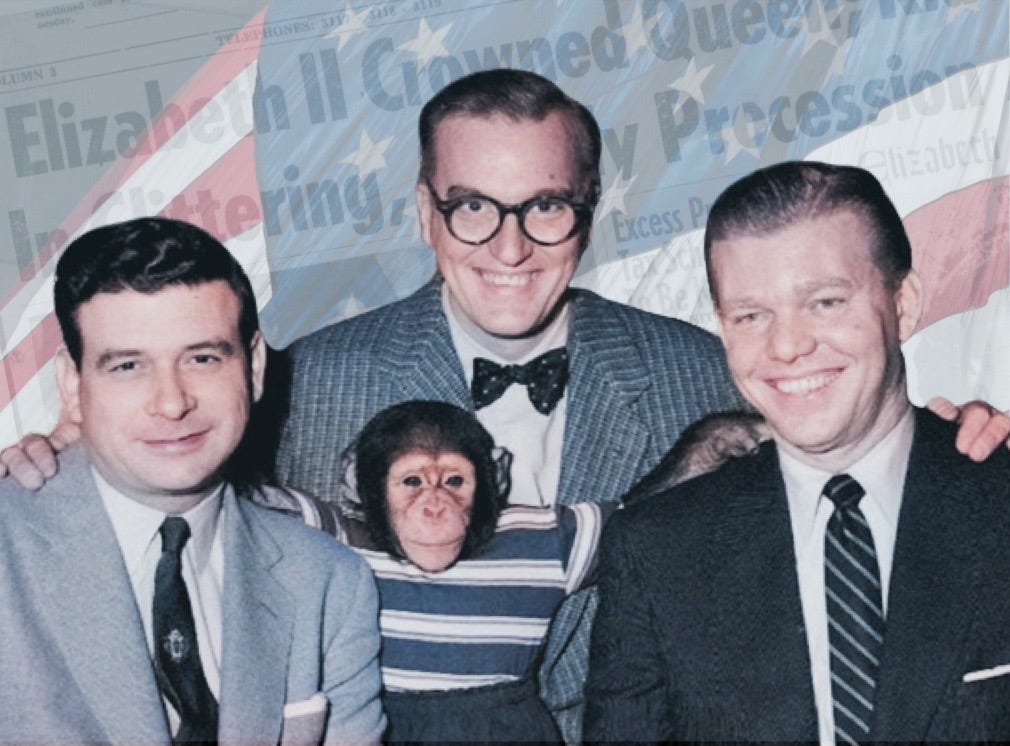

At 5:15 am (Eastern Standard Time) on the big day—June 2, 1953—CBS went on air with its first coronation day broadcast. Fifteen minutes after that, NBC’s recently launched morning news programme, Today, joined the fray. Its host, Dave Garroway, strolled jauntily into the network’s Radio City studio, wearing a bowler hat and carrying a furled umbrella, both supposedly emblematic of Britishness. He began by introducing live radio commentary from the BBC, which described the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret arriving at Westminster Abbey. This was followed by a still photograph so grainy it was hard to distinguish the Queen stepping into her ornate, horse-drawn carriage. Beaming with pride, Garroway said this picture had been wired across the Atlantic in a mere nine minutes, thanks to a miraculous gadget called a Mufax—an early type of fax machine.

A shade under half an hour later, he unveiled the secret weapon that Colledge had worked so hard to acquire. Film of the Venezuelan Canberra, shot several days previously, was accompanied by Garroway’s announcement of the coup which NBC had pulled off by chartering the plane. He revealed that his network’s footage of the coronation would be arriving in Boston only six and a half hours from then, enabling NBC to screen it at lunchtime—well before it appeared on other American networks.

Until Today went off air at 9:25 am, there were more still photos from London, supplemented by BBC radio commentary. Spliced into this was a news bulletin and a five-minute travelogue, as well as interviews with American-based guests who talked about coronation etiquette and life in the British capital. There were also live sequences in which Garroway appeared alongside what he jokily referred to as his “righthand monkey”—a mischievous chimpanzee named J. Fred Muggs, who had started working on the show only a few weeks earlier.

The chimp had been recruited in a bid to reverse plummeting audience figures by attracting child viewers to the programme and, in the process, forcing their parents to watch it. Dressed in a range of absurd clothes, Muggs provided Garroway with a comic foil whose party tricks included hammering the keyboard of a piano and dunking a doughnut. In the course of the BBC’s solemn and reverential radio commentary on the coronation service at Westminster Abbey, which began at 11:20 am Greenwich Mean Time, Garroway asked the chimp, “Do they have a Coronation where you come from?”

What NBC had codenamed “Operation Astro” was already underway by then. At a recently installed facility on Blackbushe Airfield, more or less equidistant between London and Winchester, a kinescope had copied the early stages of the BBC’s coronation coverage onto 16mm film. Once this had been edited together with footage shot by NBC’s own cameramen, positioned along the route of the Queen’s procession, it had been loaded onto the Venezuelan Canberra, which was now flying over the Atlantic.

Unknown to Colledge, though, his painstakingly constructed plans had been inadvertently kiboshed by a senior colleague at NBC. His colleague had made a courtesy call to Seymour de Lotbinière, the BBC’s Head of Outside Broadcasts, presumably to thank him for the corporation’s assistance. Operation Astro ended up being mentioned in the course of the chat. Appalled by the prospect of BBC television’s coronation footage being screened in America before it was shown in the British dominion of Canada, Lotbinière contacted the Air Ministry and persuading them to order the RAF reservist crew of the Venezuelan Canberra to fly back to London.

Just when triumph in the race with CBS seemed certain, Colledge was fed a spurious story about NBC’s plane being forced to turn around after developing a problem with its fuel feed. Fortunately for him, NBC could still emerge victorious if the DC-6B and P-51 Mustang chartered by the network could get the footage to Logan Airport before CBS.

CBC’s RAF Canberra reached Goose Bay at 1:45 pm (EST), not long after which the airliners transporting the NBC and CBS footage landed there as well. By 2:30 pm (EST), the Royal Canadian Air Force jet carrying the CBC footage was heading for Montreal, and the two P-51 Mustangs carrying the CBS and NBC footage were en route to Logan Airport. Spicing up the contest between the two Mustangs—one of them owned by the movie star James Stewart—was the fact that their pilots had finished first and second respectively in the prestigious Bendix Trophy point-to-point air race. For the pilots, this was a high-profile re-match.

But when NBC’s bosses heard that their Mustang pilot was lagging behind the rival Mustang, they quickly contacted ABC and struck a deal enabling them to share the coronation footage due to be cabled across the border from CBC’s studio in Montreal. Consequently, NBC started broadcasting this very rough-looking, unedited footage at 4:15 pm (EST)—the same time as CBC and ABC. Another nine minutes passed before CBS went on air with its own edited version of the BBC coverage.

For all NBC’s earlier disappointments, coronation day proved a great success for the network. Despite the failure of Operation Astro, the network’s coverage of events in London generated enormous publicity across America, helped to establish the Today programme as the country’s leading breakfast show, and propelled its nominal co-host J. Fred Muggs to international stardom. Yet many indignant British journalists and politicians deemed his role in NBC’s coronation coverage as symptomatic of the disrespectful attitude which had led American television networks to pepper their footage with advertising breaks. He even became the focal point of a Parliamentary debate involving the Foreign Secretary.

His celebrity status nourished by merchandising and a world tour, Muggs went on to play an unexpected part in the ensuing political tussle over whether or not to grant a broadcasting license to ITV, which would go on to become Britain’s first commercial television station. The question culminated in multiple discussions in the House of Commons, where Members of Parliament were inundated by lobbyists’ so-called green cards requesting meetings with Mr J. Fred Muggs. During the parliamentary debates about commercial television, MPs opposing the 1955 legislation needled their opponents by holding up photos of the famous chimp.

J. Fred’s tenure on the Today programme, reputed to have earned NBC $100 million, would be short-lived, though. Dave Garroway, the show’s host, allegedly became so jealous of the attention lavished on the chimp that he took to spiking the ape’s orange juice with benzedrine, his intention being to induce bad behaviour and encourage NBC to dispense with Muggs’s services.

Even without pharmaceutical assistance, Muggs was disruptive and occasionally violent. As soon as his contract expired in 1957, he was replaced by a more compliant monkey. He remained in showbiz for only a few more years, then retired to Florida with his owner. When Queen Elizabeth II celebrated half a century on the throne, he was still alive, but unavailable for comment.