Her peroxide blonde hair was the most memorable thing about her. She wore it in a fashionable style, pinned back so that it resembled a wave cresting her high forehead. Like the Hollywood actresses whose photos adorned her scrapbook, she plucked her eyebrows until there wasn’t much left of them. She also favored dark and dramatic lipstick, though in her case it drew attention to her toothy, less than perfect smile.

In futile pursuit of the showbiz career she craved, this small, plump eighteen-year-old, formerly known as Betty Jones, had striven to reinvent herself when she moved to London during January 1943. Now she called herself Georgina instead of Betty, her chosen Christian name suggestive of the upper-class sophistication to which countless British women aspired. But her change of name failed to disguise her unglamorous background, which was so conspicuous whenever she spoke, her lilting accent evocative of the coal mines, slag heaps, and grubby-faced poverty of South Wales.

Late on the afternoon of Tuesday, 3 October, 1944, the self-styled Georgina Jones was ensconced in the Hammersmith branch of the Black & White Milk Bar chain. With their sleek, monochromatic interiors, their chromium trimmings, and their counters lined with tall stools, milk bars had been a popular component of London life since the mid-1930s. They served everything from strawberry milkshakes and ice creams to sandwiches and cake. The Black & White Milk Bar, located at the junction between Queen Caroline Street and bustling Hammersmith Broadway, functioned as a social club for so-called “wideboys”—sharp-witted crooks who profited from wartime rationing, which had created an illicit market for canned food, nylons, and innumerable other scarce commodities.

Georgina was sitting with just such a wideboy. More than twenty years her senior, he was a Londoner by the name of Len Bexley. When he caught sight of a tall, slim US Army officer who had just walked in and positioned himself at a nearby table, Bexley invited him over.

The young officer moved with a nonchalant, muscular swagger that women found attractive, Georgina among them. Bexley introduced her to Second Lieutenant Ricky Allen, who had an olive complexion, dense black hair, and dark eyes, not to mention a broken nose that lent him a misleading aura of pugilistic toughness. His speech was colored by a heavy American drawl that must have reminded Jones of many of the film stars she ogled at local movie theaters. Not that her new acquaintance’s somewhat underpowered brain was capable of formulating the kind of snappy dialogue spoken by the actors she idolised.

Recently she had got into the habit of telling lies about herself in order to impress the American servicemen she met. She would tell them she had been working as “a striptease dancer”—a career option that would remain illegal in Britain for another thirteen years. And she would sometimes refer to how she was currently taking a break while she waited to find out whether she had landed a part in a London theater show. In truth, she wasn’t the person she pretended to be. She was just a part-time prostitute.

Without any reason to be elsewhere, she let the remains of that afternoon dribble away in the raffish company of Ricky Allen and Len Bexley. All three of them eventually left the Black & White Milk Bar at the same time. By then, the autumn chill outside had sharpened.

Jones and Allen parted from Bexley, then walked onto Hammersmith Broadway, the main shopping street in that neighborhood. Five years of war had reduced London’s stores to a ubiquitous level of shabbiness, characterised by sparse window-displays, flaking paintwork, and boarded-up exteriors.

Before Jones and Allen went their separate ways, the American asked if she’d care to spend that evening with him.

Something of a night-owl, Jones agreed to meet him outside the Broadway Cinema after the pubs closed.

From where she and the American had just said their goodbyes, she had a fifteen or twenty-minute walk home to the furnished room that she rented on King Street. Though she had been living in London for almost two years, big city life remained a novelty for her. The younger of two children, Jones—born Elizabeth Baker—was raised in the tiny mining village of Skewen, not far from Llandarcy Oil Refinery, where her father worked as a laborer. She often complained about how her parents had neglected her in favor of her disabled sister. As a child, she had repeatedly run away and been discovered wandering around the small city of Swansea, just five miles from her home. The authorities had wound up consigning her to a reformatory in Cheshire, where the well-meaning staff encouraged her teenage passion for dancing. Filled with dreams of showbiz stardom, she subsequently escaped, made her way south, and sampled the nocturnal glitter of London for the first time.

When she was found sleeping rough, the police sent her back to the reformatory. There, she managed to suppress her rebellious behaviour for long enough to be allowed to return to her South Wales home. Aged only sixteen, she latched onto Stanley Jones, a much older acquaintance of her parents. She appears to have regarded him as nothing more than a convenient stepping-stone out of her mundane life in Skewen. Despite her parents’ vehement opposition, she quickly married him in November 1942 while he was on leave from the British Army. He allegedly beat her up on their wedding night, the marriage remaining unconsummated before he rejoined his airborne unit.

A few days after becoming Mrs Jones, she packed a couple of suitcases and took the train to London, where she subsisted on the government allowance for which the wives of servicemen were eligible. To augment her meager income, she found casual employment. As well as working as an usherette in a movie theater, she was employed as a barmaid, a waitress, and a hostess in a “clip joint”—a seedy nightclub, where she had to coax the customers into buying her drinks at vastly inflated prices. Meanwhile, she attempted to get a dancing job in a nightclub floorshow. She only succeeded in landing a try-out for a strip-show at the Panama Club in the swanky Knightsbridge neighborhood. Her sole performance there proved so inept and graceless that it culminated in her being booed off the stage. Many months after this humiliating experience, which she blamed on the band playing at the wrong tempo, she continued to harbor theatrical ambitions. By the afternoon when she met Ricky Allen, her main hope of achieving these resided in the letters she sent to showbiz stars, begging them to give her an opportunity.

The blackout, introduced to make Britain a more elusive target for German airplanes, was diluted that night by an almost full moon. It shone down on the steps outside the Broadway Cinema, where Jones waited for Allen.

She was still there at 11.30pm—well after the agreed time. Yet there was no sign of the American.

Just as she was poised to give up, a large, khaki-painted truck came rumbling towards her. In compliance with blackout regulations, its headlamps were likely to have been masked by metal hoods, reducing them to narrow slivers. The truck stopped next to Georgina. It had a big white star—insignia of the US Army—stenciled on the door nearest to her. Through the window, she could see Allen sitting behind the wheel. She hauled herself into the seat next to him.

Moments later, he took her for a drive through West London. Being driven anywhere—even somewhere as drably familiar as that—was a rare treat at a time when petrol was unobtainable for civilians.

Punctuating the streets were overgrown bomb-sites, left over from the earlier phase of the war. Recent attacks by flame-tailed German rockets, their shuddering impact preceded by the ominous silence when their engines cut out, had also reduced numerous buildings to patches of rubble. The city’s battered streets acquired a picturesque beauty in the moonlight, filtered that night through a slight mist.

Allen steered the truck beyond the outskirts of London and into rural Berkshire. En route, movie-mad Jones declared that she’d like to do something exciting, something dangerous, “like being a gun-moll.”

“You are doing something dangerous right now, lady,” Allen replied. He went on to explain that they were riding in a stolen vehicle and that he had “gone over the hill”—deserted—from his paratroop regiment.

Jones must have felt as if she had stepped into some romantic, couple-on-the-run Hollywood movie such as Belle Starr or You Only Live Once.

Keen to impress her still further, Allen dropped a casual reference to his pre-war life as a gunman for the Chicago mob. “I moved around with the slickest outfit in the West,” he added.

While it was true that he had deserted from the US Army and had stolen the truck in which they were riding, he had never been a gangster. He wasn’t a paratrooper either. And he wasn’t the officer he pretended to be. He was, instead, a private who had been assigned to the 101st Airborne Division’s motor pool. On top of all that, his name wasn’t even Ricky Allen. It was Karl Hulten. Prior to his conscription just a few months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, this twenty-two-year-old fantasist had been a grocery store clerk, a truck driver, and a chauffeur for a limousine rental company. Until he was in uniform, he appears to have led a blameless life, working hard to support his young wife and their baby daughter.

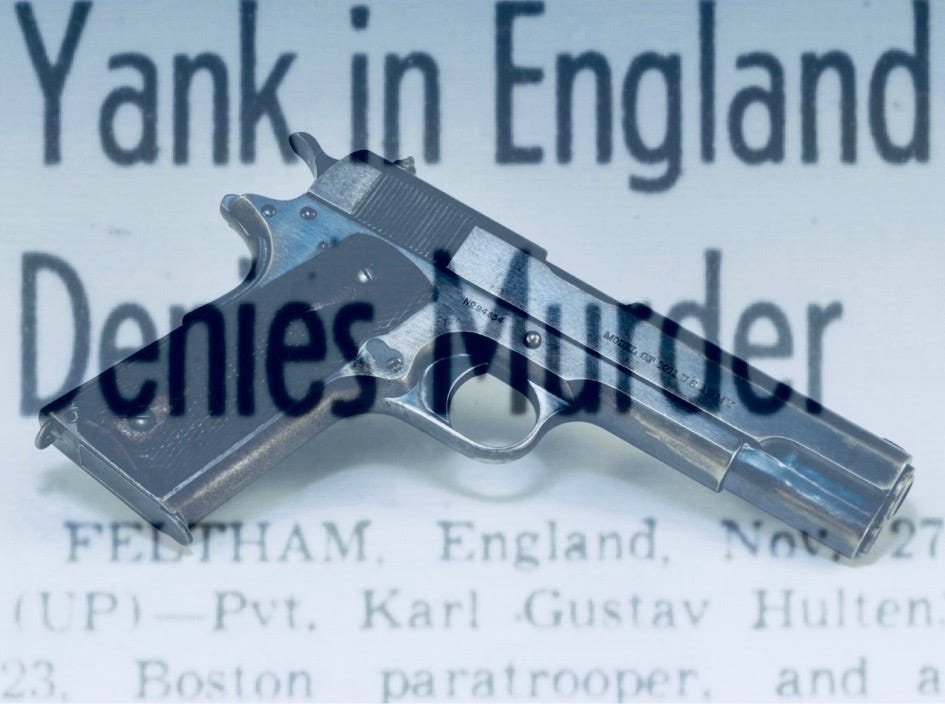

To back up what he had just told Jones about being a Chicago gunman, Hulten pulled out a Colt .45 automatic. From that moment onwards, he and Jones were committed to live out the fictional roles in which they had cast themselves.

At 1.00am or thereabouts, they were driving along a country road when they passed a solitary girl, cycling in the opposite direction. Hulten stopped the truck, turned it around, and drove past her again.

Climbing down from the truck, he stood in the road next to it and waited for her to catch up. As the cyclist attempted to go past, he lunged at her. He pushed her off her bike and snatched the handbag dangling from its handlebars. Then he got back into the truck and drove away.

Before the truck reached London, Jones searched the stolen handbag with the aid of the flashlight that she carried around during the blackout. She found a few shillings in cash. The robbery also netted her and Hulten some ration coupons. Since these could be exchanged for clothes—a very limited commodity in wartime Britain—they were worth about a pound. This raised the proceeds of the robbery to the equivalent of only about $70 in 2021 currency. Not exactly the sort of figure you’d associate with the big-time crime Hulten had bragged about.

The two desperadoes were back in Hammersmith as dawn approached. Georgina returned to her room on King Street while Hulten slept in the back of his truck, which he left in a parking lot at the back of the Gaumont Palace movie theater.

Dressed in a US Army-issue brown leather jacket that emphasised his trim waist, Hulten collected Jones from her lodgings next day—Thursday, 5 October, 1944. The daylight had a hazy quality, thanks to the dust from acres of rubble-strewn bomb-sites.

On their second date, Hulten took Jones for a meal, followed by a visit to the enormous Gaumont Palace, which was just down the street from the milk bar where they had met. At the final credits, they walked over to the stolen truck.

Jones had come well-prepared for the dipping temperature. She had on a baggy fawn topcoat with a tie-belt. She also wore a black scarf over her hair.

Probably anxious to show off in front of the doting Jones and make up for the previous night’s embarrassment, Hulten talked about committing another robbery. Just as he had done on their first evening together, he took her out of London and into the foggy Berkshire countryside. He pulled up next to a pub-hotel, which provided a convenient target for his next crime, though he soon lost his nerve. On the grounds that he’d seen someone watching him, he sped off.

They were now heading back the way they had come. As they ploughed through the fog, which dissipated when they got closer to London, Jones appears to have suggested that they hold up and rob a taxi driver.

Instead of returning to Hammersmith, Hulten drove into the moonlit West End, where he tailed a cab going north up the Edgware Road. Just after 2.00am, the cab stopped at an address in the outer suburb of Neasden. A woman disembarked and went into her home. Just as the cab started to turn around, Hulten used the truck to block it. He then jumped out, pointed his handgun at the cabbie, and demanded money.

The cabbie said he didn’t have any cash, because he was still on his first job that night.

Peering into the back of the cab, Hulten came face to face with a second passenger—a twenty-two-year-old US Army lieutenant, who was brandishing a handgun. Hulten sprinted back to the truck and made a panic-stricken getaway.

He and Jones retraced their route onto the interminable Edgware Road. They soon abandoned the idea of holding up a taxi cab. Instead, they decided to find another young girl and rob her.

Towards the Marble Arch end of Edgware Road, Jones spotted a suitable, lone girl. “Stop!” she said to Hulten, who had already driven past their prey. He obediently put the truck into reverse and braked when he drew level with her.

She was every bit as slight and small as Jones. She was about the same age as well. In one hand she carried a big brown suitcase, fastened with rope.

Calling out to her, Hulten asked where she was going.

A more worldly girl might have ignored him. This one replied that she was heading for Paddington Station to catch a train. She explained that she needed to get to Bristol.

Hulten told her that he and Jones were driving to Reading and could give her a lift there. It was, after all, on the same rail line as Bristol.

The girl accepted their offer. She was helped into the truck by Hulten. He also stowed away her suitcase. She sat in between him and Jones, who chatted amiably with her as they drove down Edgware Road. Putting on an American accent that was plausible enough to fool the girl, Jones talked about making a point of avoiding London, because she’d been robbed on her last visit. She gestured towards Hulten and referred to how the pair of them were due to celebrate their third wedding anniversary.

Hulten contributed little to the conversation, preferring to concentrate on navigating across West London. They soon reached the countryside beyond. As they drove through Runnymede Park, he suddenly announced that one of their tires felt as if it had gone flat. He maneuvered the truck onto the grass verge and hopped out.

Jones and the girl accompanied him as he strolled around the vehicle, pretending to inspect each of its ten tires. His inspection concluded with him declaring that they could delay changing the defective tire until they arrived in Reading.

So they returned to their seats and resumed their journey.

“It’s no good,” Hulten said after they had gone just a short distance. “I’ll have to take the wheel off.”

He performed a sharp U-turn and went back to the strip of grass near to where they had parked a few minutes earlier. Before long, all three of them were standing beside the truck. Hulten—who had already picked up a length of iron pipe—lent over to Jones and surreptitiously instructed her to make sure that the girl was standing with her back to him.

Jones agreed. In an effort to distract the girl, she gave her a cigarette. At the next opportunity, Jones whispered to Hulten that she thought the girl was “wise” to what they were doing.

Hulten told Jones to climb into the back of the truck and get the wheel-blocks, which he would need when he changed the tire. As Jones fetched them, he swung the iron pipe at the girl. He struck her on the side of the head, yet the blow was not hard enough to knock her out.

Discarding the iron pipe, Hulten grabbed her throat and pushed her over. She fell face-down. Hulten planted his left knee on the cold ground and his right knee in the small of her back. The girl could now do nothing but flail around with her right arm as he tightened his grip on her neck.

Hulten directed Jones to hold the girl’s arm. Jones obliged by kneeling on it. She then searched the girl’s coat pockets, from which she plucked a handful of coins. By that time, the girl was completely motionless. Jones took the opportunity to steal her coat.

While Hulten hooked his hands under the girl’s shoulders, Jones lifted up her inert legs. Together, they carried the body over to the nearby river. They dropped the girl into the water about three feet from the edge. Hulten also lobbed the iron pipe into the river.

Back in Hammersmith, they rounded off their second date with a visit to one of the city’s cheap all-night cafés, after which Jones took Hulten home with her. In the privacy of her lodgings, they could examine the contents of the dead girl’s suitcase. Jones was rewarded with a rationing-era treasure trove—orange satin pajamas and four pairs of silk underwear.

She and Hulten remained in bed until the middle of the following afternoon. His US Army uniform was bloodstained, so Jones fetched his spare clothes, which he kept in a bag at Hammersmith Metropolitan Station’s cloakroom.

Attired in a fresh uniform, he showed his gratitude to Jones by promptly going off to meet another girlfriend—sixteen-year-old Joyce Cook—at the bakery where she worked. Cook had no inkling of anything about his parallel lives as a brutal criminal, as Jones’s lover, as a husband and father.

Like a normal young courting couple of that era, Hulten and Cook went to the movies. And then they spent the remainder of the evening at her family’s convivial home.

It was not until about 11.30pm that Hulten travelled the mile-and-a-half from there to Jones’s lodgings at 311 King Street. Obviously emboldened by the complete absence of any repercussions from what they had done to the girl from Bristol, they made plans to hijack a cabbie.

Hulten and Jones began by walking east along King Street, which was lit by the waning moon. Half-a-mile down Hammersmith Road, they ducked into a doorway opposite the huge Cadby Hall office block and industrial plant. From this vantage point, they spotted an approaching car. Jones reckoned it was a taxi, but Hulten was convinced that it was a US Navy staff-car. He stayed hidden in the shadows while Jones stepped out and shouted, “Taxi!”

The vehicle was a gray 1936 Ford V-8 with no markings to indicate that it was either a cab or a staff-car. It braked sharply, enabling Jones to go over and speak to the driver, the most conspicuous facet of whose weatherbeaten features was a dimpled chin. “Are you a taxi?” she asked.

He replied that he was a private-hire driver—a perfectly legal breed of unlicensed cabbie. “Where do you want to go?” he added.

“Wait a minute.” She hurried back to Hulten and told him that the vehicle was a private-hire car.

Unnerved by his experience in Neasden the previous night, Hulten asked how many passengers were already in the cab.

Just the driver, Jones responded.

Suitably reassured, Hulten ventured out of the doorway with Jones. They told the cabbie that they wanted to go to King Street.

The cabbie said the journey would cost ten shillings.

Once they had agreed to that, Hulten and Jones got into the back seat of the Ford. Hulten positioned himself directly behind the cabbie, who accelerated down the road. When they reached King Street, Hulten and Jones gave no indication of where they wanted him to stop. They just let him carry on driving in that direction. He soon said, “We’ve passed King Street. Where do you want to go?”

“It’s further on,” Hulten replied. “I don’t mind paying more.”

Hulten and Jones appear to have directed him to take a lefthand turn. As they approached a roundabout, Jones heard a distinctive, metallic clicking noise from Hulten’s handgun.

“This is the Great West Road,” the cabbie said.

Either Hulten or Jones must have asked him to head towards the suburb of Brentford. Hulten told the cabbie to drive slowly. A few hundred yards down the road, they approached a railway bridge.

The cabbie gave every indication of being annoyed. He explained that he needed to go and collect a fare from Maidenhead—about seventeen miles from their current location.

Hulten placated him by saying, “We’ll get out here.”

No sooner had the Ford halted near to where the bridge crossed the railway line than the cabbie reached across the front passenger seat, ready to open one of the rear doors for Jones. Even though Hulten had warned her that his Colt .45 would make a loud bang when it went off, she was unprepared for just how thunderous it was. It temporarily deafened her in one ear. The sound of the gun was accompanied by a bright flash that pierced the semi-darkness inside the car, where soft moaning noises were audible from the driver’s seat.

First striking the cabbie in the back, the bullet had grazed his spine. It had then passed through one of his lungs and caused severe haemorrhaging.

“Move over or I’ll give you another dose of the same,” Hulten said to the cabbie, who dragged himself over the front passenger seat.

Still gripping the Colt .45, Hulten took the cabbie’s place behind the wheel. As Hulten drove over the railway bridge, he told Jones to rip down the blind covering the rear window. He wanted her to check whether or not anyone was tailing them.

Peeling back the righthand corner of the blind, she inspected the highway unwinding behind them. Nobody was in pursuit.

While Hulten drove through the West London suburbs, Jones searched the cabbie’s pockets. She could hear him breathing in short, pained gasps. From his pockets, she harvested a fat brown fountain pen, a silver mechanical pencil, a fancy cigarette case, and an equally expensive cigarette lighter. His pockets also yielded a driving license, a chequebook, a handkerchief, some photos, letters, ration coupons, and small change, plus a wallet containing four £1 bills. In addition, Jones pulled out an identity card, from which she discovered his name—George Edward Heath. She threw the photos and letters out of the window and kept the rest.

Beyond Twickenham and the last of the city’s suburbs, Hulten turned off the highway and down a side road, which led through a stretch of scrubby countryside. He drove onto the grass that ran alongside a ditch. Most likely assisted by Jones, he dragged the cabbie’s dead body out of the car and rolled it into the ditch.

Hulten complained about having blood smeared over his hands. Jones gave him the cabbie’s handkerchief. He used it to wipe himself down before getting back into the car.

Jones sat next to him in the front. He warned her to be careful of leaving fingerprints.

On their way back to London, she hunted for the bullet that had killed the cabbie. She spotted it on the floor, only inches from her feet. Picking it up, she handed it to Hulten.

He drove them to the parking lot behind the Gaumont Palace movie theater. He and Jones then worked their way around the vehicle, trying to clean off whatever fingerprints they had left. Undaunted by the murder they had just committed, they headed from there to an all-night café, where they ate some sandwiches before going back to Jones’s room.

They didn’t get up until about lunchtime on Saturday. Hulten started the day by taking the stolen wristwatch over to the local barbershop where he was a regular, his boastful yarns about his escapades as a gangster earning him the nickname, “Chicago Joe.” Without bothering to wait his turn, Hulten cut into the flow of customers and asked Maurice, the assistant barber, if he’d like to buy a wristwatch. Maurice handed over five pounds and pocketed the watch.

Later that afternoon, Hulten and Jones met up with Len Bexley, who had introduced them only four days earlier. Hulten sold him George Heath’s mechanical pencil, fountain pen, and silver-plated cigarette-lighter.

Flush with the profits from all these sales, Hulten and Jones took advantage of the dry weather by joining Bexley for a trip to the nearby White City Stadium—a huge, largely roofless bowl, which hosted what was, in those days, the popular sport of greyhound-racing. Jones used the money taken from the dead cabbie to place a series of bets. These netted her a tidy profit.

Unlike Bexley, she and Hulten didn’t stay for the full program of races. Instead, they went for something to eat at a milk bar, probably the Black and White in Hammersmith.

Encouraged by the absence of any newspaper reports about the murder of George Heath, they felt safe enough to retrieve his Ford V-8 from the parking lot where they had abandoned it. They decamped from the milk bar to a movie theater in Victoria, a neighborhood almost five miles from their normal haunts.

The movie theater advertised screenings of a hit Hollywood crime drama, starring Deanna Durbin and Gene Kelly. “Love was her crime! Love was her punishment!” declared the posters for the misleadingly titled Christmas Holiday.

Arm in arm, Jones and Hulten watched this tale of a beautiful young woman dragged down by a homicidal husband. Jones wore a corsage that Hulten had, in a romantic gesture, bought her earlier that evening.

Hulten went out next day, leaving Jones to spend most of it alone in her room. By 8.30pm, he still hadn’t returned, so she walked over to the Swan, a cosy old pub opposite Hammersmith Metropolitan Station. Among the customers, she noticed a man in a blue-gray RAF uniform. She went up to him and engaged him in conversation. He introduced himself as Mac. The two of them wound up moving to another pub, where they knocked back a few drinks.

At about 10.00pm, Jones took Mac home to her room, presumably for some commercial sex. Booze and memories of the previous night’s film apparently loosening her tongue, she told Mac about witnessing the murder of the taxi driver.

Her companion inquired what the motive had been.

Robbery, she replied.

Mac asked if she wanted him to go to the police about it.

She said she didn’t.

Yet he insisted on giving her his name and address. He stressed that she should contact him if she needed help.

His offer coincided with the moment when Hulten turned up at her King Street address. Before Mac left, she told him that Hulten was the man who had shot the cabbie. Mac’s presence may be what alerted the somewhat slow-witted Hulten to the fact that she was, in the slang of that period, “a commando”—a prostitute.

Jones and Hulten then walked over to the Gaumont Palace’s parking lot, intent on checking whether the dead cabbie’s Ford V-8 was still there. When Hulten saw the car, he assured Jones that there was no need to worry. He said the body couldn’t have been discovered, because the newspapers hadn’t mentioned anything about it.

From a nearby US Army truck, parked nearby, Hulten stole a couple of five-gallon cans of petrol. He and Jones followed the theft by driving into the West End, where he promised to steal a fur coat for her. To that end, he parked close to the side entrance to the deluxe Berkeley Hotel on Piccadilly.

“Babe, pick out a fur coat, and I’ll get it for you,” he told Jones. “Any one you fancy is yours…”

“That’s the one I want,” Jones said, pointing at the white ermine sported by a petite woman who had strode out of the foyer.

Clutching his handgun, Hulten sprang out of the car and marched towards the woman as she descended a short flight of steps. He aimed his Colt .45 at her, prompting her to scream. The noise attracted one of the police constables responsible for patrolling that part of town. He showed up just as Hulten was tugging the fur off the woman’s shoulders. Hulten rushed back to the waiting Ford V-8, in which he and Jones made their escape.

They rounded off their date with another late night meal, this time at a café in Shepherds Bush. Then they headed back to Jones’s lodgings and parked the car behind a brick-built air-raid shelter that blocked a section of King Street.

The morning of Monday, 9 October, 1944 was overcast and drizzly, so they didn’t miss much by staying in bed until around 2.00pm. Hulten went out a little later, saying that he’d return at five-thirty that afternoon. Jones—whose room overlooked the street—watched him drive away.

Instead of returning to King Street at the specified time, Hulten collected Joyce Cook from her work-place and gave her a lift back to her parents’ home on Fulham Palace Road. He parked the car opposite and joined her inside.

At 8.00pm, the attention of a passing police constable was caught by the Ford V-8’s headlamps, which Hulten had forgotten to switch off. The constable took a closer look. He recognised the vehicle’s number-plate, which had been circulated around all British police forces. The car belonged to George Heath, the murdered cabbie whose corpse had been discovered less than twenty-four hours earlier.

Hurrying to the nearest telephone, the constable alerted Hammersmith Police Station. Within minutes, several of his colleagues had the so-called “murder car” under surveillance, but another hour drifted past before Hulten emerged.

Probably having read newspaper reports about the discovery of George Heath’s body and the resulting investigation, Hulten approached the Ford V-8 with newfound wariness. In case the police were lurking in the street outside, he had already cocked the hammer on his loaded Colt .45, which he carried in his hip pocket.

As he settled himself behind the wheel of the dead man’s car, he was dragged out of it by a couple of police officers. Next moment they had him pinned him against a neighboring wall. They searched him and confiscated his gun.

His American citizenship left the police in a frustrating position, though. Under the terms of the United States Visiting Forces Act, which the British wartime government had pushed through Parliament “in the interests of good feelings between the two countries,” members of the American military arrested for alleged offences against British subjects had to be handed over to the US authorities for questioning and trial. Not that American military tribunals were known for their leniency. Prior to Hulten’s capture, fourteen US servicemen had been executed after being found guilty of the murder or rape of British civilians.

When Hulton failed to return to her lodgings that night, Jones must have wondered what had happened to him. It may not have crossed her mind that he was being held at Hammersmith Police Station.

The following day Lieutenant Robert De Mott, a former Colorado lawyer, now serving with the US Army’s Criminal Investigation Department, arrived there and questioned him. Pivotal to the interrogation was the Ford V-8, which Hulten had been driving. He denied any involvement in Heath’s murder, and claimed to have found the car abandoned in the town of Newbury.

Towards the end of that afternoon, Lieutenant Mott arranged to have Hulten placed in American custody on an initial charge of desertion. Hulten was then transferred to the US Army’s CID Headquarters near Piccadilly. There, Mott employed what Hulten would later describe as “American methods of interrogation.”

Harangued and possibly beaten, Hulten changed his story. He said he’d discovered the Ford V-8 in a Hammersmith parking lot on the Monday after Heath’s murder. And he told Mott that he’d been at Georgina Jones’s place on the night of the killing.

Mott persuaded Hulten to show him where Jones lived.

On the morning after the interrogation, Mott drove Hulten to King Street. With them were Chief Inspector Wilfred Tarr and Detective Inspector Albert Tansill, the two British detectives in charge of investigating the cabbie’s death.

Jones was still in bed when Tarr and Tansill entered her room. They asked if she was acquainted with an American soldier.

“Yes, his name is Ricky,” she replied. “He stayed with me several nights.”

The detectives then took her to Hammersmith Police Station, where they interviewed her about the night of the murder. She sought to incriminate Hulten by saying that the two of them had gone to the movies, after which he had departed for three hours before they spent the night together at her lodgings.

Detectives Tarr and Tansill saw no reason to detain Jones, so she was permitted to leave the police station. Before going home, she called round to a laundry to pick up her washing. At the counter, she bumped into Henry Kimberly, a temporary wartime police officer whom she had met when she used to work at a local café. Shocked to see how pale and weary she looked, Kimberly asked if she was alright.

“Since you last saw me, I’ve turned into a bad girl. I’ve been drinking a lot.”

“Yes, you look tired.”

She explained that she had spent the past few hours at the police station, answering questions about the murder of George Heath.

“What have you got to worry about? You had nothing to do with it, did you?”

“I know the man they have got inside. It would have been impossible for him to do it as he was with me all Friday night.”

“Well, you must stop this worrying and try and get some rest. You really do look worn out.”

She told Kimberly that he wouldn’t be able to sleep at night if he’d seen what she had seen.

“The best thing for you to do is to go back to the police station and tell the truth.”

Unsurprisingly, she failed to take up his suggestion when she left the laundry. Kimberly, however, reported their conversation to Detective-Inspector Tansill.

Tansill drove Kimberly over to Jones’s lodgings that afternoon. “Why did you bring the inspector here?” she asked Kimberly.

“It’s because of what you told me in the cleaner’s shop. I think you should tell him the whole truth.”

For the second time that day, Jones found herself at Hammersmith Police Station, where she made another statement. “I was in the car when Heath was shot,” she admitted, “but I didn’t do it.” She said that she had kept quiet about it because she was terrified of Hulten, who had once held a gun to her head. In passing, she asked the detectives if they had found the body of the young girl he had attacked.

“What girl?” one of the nonplussed detectives answered.

“The one that Ricky and I robbed on Thursday night by the river. There are some of her things in my room.”

Around midnight, Hulten was confronted by Jones’s latest written statement. He reacted by admitting to the attack on the young girl. He also confessed to shooting George Heath, yet he insisted that he’d never meant to kill the cabbie. Referring to Jones, whom he described as being aroused by violence and obsessed by the idea of herself as a gangster’s moll, he said, “If it hadn’t been for her, I wouldn’t have shot Heath.”

Despite Hulten’s confession, the case against him and his accomplice still presented unique problems for the British and American authorities. Initially, plans were made to postpone Hulten’s appearance in front of a military court until after Jones had been tried. That opened up the awkward and embarrassing possibility of one of them being acquitted and the other executed for the same crime.

By waiving the right to prosecute Hulten themselves, the US military could avoid risking even the possibility of such a scenario. On the other hand, the news that an American citizen was being handed over for trial by a foreign government might affect the prospects of the incumbent, Franklin D. Roosevelt, in the looming US Presidential election. Rather conveniently, the announcement that Hulten would be tried by the British was delayed until after Roosevelt’s 7 November, 1944 election victory.

The better part of three more weeks passed before Hulten and Jones appeared in court in Staines, the town closest to where George Heath’s corpse had been discovered. Both of the defendants were charged with his murder and committed for trial at the Old Bailey. If they were found guilty, they would face a death sentence. Mysteriously from their point of view, the prosecutors made no mention of the girl whose body they had dumped in the river.

In the run-up to their trial, Hulten and Jones were detained at separate London jails. Hulten ended up at Brixton while his girlfriend languished behind bars at Holloway, her blonde hairdo gradually tarnished by dark roots. She maintained a delusional belief that the jury would acquit her, even though the prosecution had no shortage of evidence against her.

The choice of Ethel Lloyd Lane as her lawyer represented a British legal milestone. Lane would be the first female barrister to defend a client charged with murder.

By the time Jones was escorted into the dock on Tuesday, 16 January, 1945, abundant press coverage of the case ensured that a long queue of people, anxious to get into the public gallery, were standing in the misty street outside the Old Bailey. There was similar competition for seats on the press benches, where American reporters rubbed elbows with their British counterparts.

Jones’s parents, whose travel expenses had been paid by a British newspaper, were also there to see her and Hulten plead “Not guilty.” Over the ensuing five-day trial, during which both defendants were summoned to the witness-box, they provided differing accounts of what had occurred in Heath’s cab.

Hulten portrayed the murder as an accident. His assertion was that he had only ever intended to shoot through the door. He said he wanted the impress Jones and intimidate Heath, but his plan had gone wrong when Heath had suddenly moved into his line of fire. If Hulten could convince the judge and jury of that, he would have his murder charge downgraded to manslaughter, in the process sidestepping the death penalty.

Though Jones admitted to being in Heath’s car on the night of the murder, she was adamant that she had done nothing to assist the crime. She clung to her story about being a helpless stooge of the sadistic Hulten, who had threatened her with his handgun. She even claimed that she had only got into Heath’s taxi because she thought Hulten intended to take her back to her lodgings.

Under cross-examination, she and Hulten kept contradicting themselves, changing their stories, and attempting to shirk the blame for what had happened. Their testimony achieved the rare distinction of seizing the headlines from the ongoing war with fascist Germany and Japan—a war without which Hulten and Jones were unlikely to have crossed paths.

Due to the murdered cabbie’s dimpled chin and ink-stained fingers, headline-writers referred to the case as “the cleft-chin murder” or “the murder of the man with the ink-stained fingers.” Blending gleeful prurience and moralistic scorn, the accompanying coverage emphasised the pulp fiction components of the relationship between “Chicago Joe” and the Welsh former stripper dubbed “Blondie.” To many British reporters, Jones embodied the morally repugnant wartime figure of “the Good Time Girl,” viewed as a product of the malign influence of American popular culture on their society.

Across the English Channel, the novelist Nancy Mitford confessed to scouring the Paris news-stands in search of each installment of the trial and reading these with “utter fascination.” The drama moved towards its climax on Tuesday, 23 January, 1944 when the judge summarised the defense and prosecution cases for the benefit of the jurors. Improbable though it was that the jury would find the defendants not guilty, the police were already making contingency plans.

That Tuesday, several new witnesses were ushered into the court—witnesses capable of supporting a fresh indictment on a charge of attempted murder. Hulten and Jones must have been shocked by the sight of one of those witnesses.

Sitting a matter of yards from them was Violet Hodge, the eighteen-year-old whom they had picked up on Edgware Road and apparently murdered. Unknown to them, she had been revived by the cold water when they had dumped her motionless body in the river. After staggering to a nearby house for help, she had been hospitalised. She had also given a statement to the local police, whose investigation had got nowhere until Jones had mentioned the girl to Inspectors Tarr and Tansill.

But the prosecutorial safety net proved unnecessary, because the jury took only ninety minutes to find Hulten and Jones guilty of murder. Alongside its verdict, the jury used its discretionary option to recommend mercy in the sentencing of Jones. The judge said that he would pass on this recommendation to the Home Secretary.

In the wake of the judge sentencing her and her former boyfriend to death, Jones turned towards Hulten and yelled, “Lies, lies, all lies! Why didn’t he tell the truth?” As she was led out of the dock, she started screaming in terror and disbelief.

Hulten and Jones’s lawyers identified supposed procedural failings in the conduct of the trial. These provided a pretext to urge the Court of Appeal to quash the verdict and grant a re-trial.

Both of their appeals were, however, rejected in late February 1945. Permission was then sought from the Attorney-General to take the appeal to the so-called Law Lords—a panel of judges appointed to the House of Lords, Parliament’s second chamber.

Prior to the Attorney-General delivering his ruling, the famous playwright and provocateur, George Bernard Shaw, weighed into the debate with a letter to the London Times. Shaw applauded the judge’s decision to hand a death sentence to Jones as well as Hulten. He described Jones as “a girl whose mental condition unfits her to live in a civilized community.” All such “idiots and intolerable nuisances” should, he argued, be subject to “state-controlled euthanasia.”

The crime writer F. Tennyson Jesse—author of a popular fictionalised account of a previous killer-couple cause célèbre—immediately rebuked him. She pointed out that “state-controlled euthanasia […] brings us at once into Hitler’s area, which we must avoid.”

Only a day after Tennyson Jesse’s intervention, the Attorney-General refused to sanction an appeal to the Law Lords. He ruled that the execution of Hulten and Jones should proceed on Thursday, 8 March, 1945. The couple’s sole prospect of avoiding the noose now lay in appealing for clemency from the Home Secretary.

Herbert Morrison, who held that post within the wartime coalition government, had already been deluged with letters about the case. Some of these demanded that both Hulten and Jones should hang. Others urged him to grant reprieves. Pleas for mercy came from Hulten’s wife and mother, not to mention the Senator representing their home state of Massachusetts.

Morrison even found himself under pressure from female factory workers in the north of England, who threatened strike action if Jones was reprieved and Hulten hanged. The pressure took a political form, too. While the US Ambassador to Britain implored the Home Secretary to spare Hulten, Ernest Bevin—who was a cabinet colleague of Morrison’s—indulged in Welsh solidarity by arguing on behalf of Jones.

With just a day to spare before the scheduled executions, Morrison ruled that Hulten should hang and Jones should be reprieved. There was no obligation on Morrison to reveal the reasons for his decision, but he explained to the US Ambassador that her youth was the main factor. Her gender must have also contributed to Morrison’s ruling. Statistics from the first half of the twentieth-century show that successive Home Secretaries were much more likely to grant reprieves to women.

Reprieving Jones proved immensely controversial. In Neath, the town nearest to where she had been born and raised, walls were chalked with drawings of the gallows alongside the line, “she should hang.”

Early on the morning of his execution, Hulten—who had turned twenty-three just five days earlier—was playing chess with a warder at Pentonville Prison in North London. The imminent hanging had provoked a demonstration by several hundred anti-capital punishment protesters, who gathered outside the gates of the jail. Foremost among the demonstrators was the flamboyantly black-clad Violet Van der Elst, a onetime domestic servant who had become an immensely rich businesswoman. “You let the girl off, but you hang the man! It is a damned shame!” she chanted.

As the scheduled 9.00am hanging approached, she and a fellow campaigner drove a refuse truck at the prison gates, but they were intercepted by a police vehicle. She and the driver of the truck were arrested.

Oblivious to this tragi-comic drama, Jones was receiving psychiatric treatment at Holloway Prison. The authorities subsequently transferred her to the young offenders’ section of the women’s jail at Aylesbury, where she received numerous letters proposing marriage. Two of the would-be bridegrooms even visited her, one of them clutching an engagement ring.

Interest in her and Hulten remained so high that two books about their crime spree were published within months of the execution. The case also spawned a famous George Orwell essay, entitled “The Decline of the English Murder.” In this tongue-in-cheek lament for the era of middle-class Victorian and Edwardian psychopaths, Orwell decried the case as an arbitrary and “meaningless story,” the product of the Americanised wartime world of “dance-halls, movie-palaces, cheap perfume, false names, and stolen cars.” He argued “it is difficult to believe that this case will be so long remembered as the old domestic poisoning dramas, product of a stable society where the all-prevailing hypocrisy did at least ensure that crimes as serious as murder should have strong emotions behind them.”

Within six months of the publication of Orwell’s essay in the 15 February, 1946 issue of Tribune, another of that left-wing magazine’s leading contributors had found emotional resonance in the experiences of Hulten’s former girlfriend. The writer in question was the war correspondent-turned-bestselling novelist, Arthur La Bern, now mainly remembered for writing the novel on which Alfred Hitchcock based the 1972 thriller, Frenzy. La Bern’s second book, Night Darkens the Street, which came out in 1947, offered a vivid, fictionalised portrait of Jones, renamed Gwen Rawlings.

Not long after its publication, the novel formed the basis for Good Time Girl, a controversial British movie that further rebutted Orwell’s dismissive attitude to the case. Despite being framed as a cautionary tale against adolescent rebellion, its producers were exhorted by the Home Secretary to re-edit it. The movie also sparked condemnation from film critics and protests from women’s groups.

Six years after its release, the model for its central character was freed on parole. “I have sworn to spend the rest of my life in repentance,” she told a newspaper reporter before stepping out of the limelight she had once sought. Even so, the story of her anarchic and bloodthirsty romance refused to accompany her into obscurity.

At the start of the 1990s, that relationship was depicted in Chicago Joe and the Showgirl, an appropriately Anglo-American movie, starring Kiefer Sutherland and the British starlet, Emily Lloyd. The movie made little commercial impact, though it seems to have helped to revive interest in the case.

Over recent decades, the tale of what one academic branded “the blackout Bonnie and Clyde” has become enshrined in the history of wartime Britain. For all the reasons Orwell assumed that the story would be swiftly forgotten, it is now synonymous with the tawdry world of blackout London, the world of bomb-sites, V-1 rockets, and wide-eyed British girls jitterbugging with American servicemen.